Aaron’s Top Ten of 2018

It just isn’t fair to pick only 10 films to represent the best of 2018—this is a year that could easily warranted a Top 20. In fact, I could completely rearrange this list, including 10 different titles, and be completely happy with it. As I was re-watching films at the end of the year to get them fresh in my mind, I actually wrote up for more than ten, not knowing which would make it. That’s a pretty good sign of a very good year in cinema. Looking at the films that did end up making my list, there are a few obvious trends. First is the work of black filmmakers, who told vital stories about their place in American society. Films like The Hate U Give, If Beale Street Could Talk, Widows, and even Black Panther are great examples of this that are not on my list. Another major trend shows that 2018 is perhaps the greatest overall year for female filmmakers with works ranging from humanist mood pieces to violent genre films. Finally, though it doesn’t exactly come through in my list, it was an incredibly deep year for non-English language cinema. Burning, Happy as Lazzaro, Roma, Cold War, Custody, The Guilty, and Western are all among the year’s best. Not among the 201 releases I saw this year: Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda, Capernaum, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, A Bread Factory, The Captain, Bisbee ‘17, The House That Jack Built, Destroyer, The Sisters Brothers, Border, A Private War, The Wife, and about 800 others.

10. Sorry to Bother You

It makes sense that the wildest movie of 2018 is the most confident. Boots Riley’s audacious debut film is all over the place, full of seemingly millions of ideas and plot turns, but so clear in authorial voice. Without knowing Riley’s art as a writer and musician, Sorry to Bother You exudes a singular style that even without the social commentary is just fun to watch. There are stylistic touches of Gondry and thematic touches of Gilliam, making for a fast and wild visual and tonal style. While this style overwhelmed some of the messaging on first-viewing, the anti-corporation/pro-labor and racial themes feel less jumbled on repeat—the many different representations of black bodies and black art scattered throughout the film, for example, come into a better connected focus. Lakeith Stanfield has been an actor I’ve loved ever since his supporting role in Short Term 12 and after more supporting work in Atlanta and Get Out, he was more than ready for a lead breakout. Sorry to Bother You serves his offbeat energy well, especially in the film’s crazy third act, where his character spills into a world that he can’t comprehend. Really, though, Boots Riley is the star here and I just hope he continues to make films. Sorry to Bother You was obviously a passion project, one he spent years working on across entertainment media, so I frankly wouldn’t be surprised if he never makes a film that feels as personal or vital. Even so, purely as a visual storyteller, he has a lot to offer and I very much doubt he’s willing to tell stories that play it safe.

9. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse

A few weeks ago, I tweeted that this would probably be the first year where a documentary or animated film would not make my top ten (in fact, two animated films made my top 10 in 2017). I thought about adding an asterisk to that statement that I had yet to see Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse, which had just begun getting raves, but I decided to stay with the provocative statement and let it play out. While a documentary couldn’t pull it out (it was a disappointing year for me on that front overall), I found the hype on the Spider-verse to be very, very real. OK, maybe it isn’t the best superhero movie ever—at the very least, we need some time to parse that out—but this is certainly one of the richest artistic and entertaining films of the year. The animation style is bold and loud and bright and wholly unique. The comics-come-to-life form brings a beautiful texture, at times giving it almost a stop motion look. Then, as the film brings in characters from its multidimensional plot, each have their own signature animation that both pops off the screen but blends into the frame. The look of the film could have been completely disjointed, let alone hectic, but it all works together as a new pop art form. From a plot perspective, it is amazing just how digestible the film is. Many superhero films have crazy intricate plots that don’t hold up to any sort of speculation (what is that big McGuffin and how does it actually work?); Into the Spider-verse embraces science, doesn’t water it down, but makes it accessible. I don’t know if I could sit here and explain to you ins-and-outs of the particle collider thingamajig, but it wasn’t a distracting mess in the moment.

8. Paddington 2

The first 2018 release I saw was good enough to stick on my best of the year list in part because of other circumstances throughout the year. For most people, 2018 was pretty terrible—I don’t think I have to get into why—and Paddington 2, a sequel about an anthropomorphized bear living in London, is something of a shining light of goodness and kindness. Paradoxically, it is also a movie where the main character is framed for a crime, sent to prison, encounters a number of rough types (presumably murderers and rapists), breaks out, etc. But there is so much warmth in the character of Paddington and he is so well realized on the page, in the effects, and in the vocal performance by Ben Whishaw, that I never once was taken out of the film in any cynical way. Director Paul King, who is perhaps most known as a major player in the very weird British comedy The Mighty Boosh (which was also a discovery for me in 2018), brings a comic sensibility and dedication to artistic design that is reminiscent of but not merely a copy of the works of Wes Anderson. A strong ensemble cast features Sally Hawkins, Hugh Bonneville, Julie Walters, Peter Capaldi, Noah Taylor, and especially Brendan Gleeson as the convict with a heart-of-gold and Hugh Grant as the flamboyant and surprisingly sinister villain. And personally, with the birth of my first child in 2018, I couldn’t help but cherish the idea of watching Paddington 2 with Riley for years to come.

7. BlacKkKlansman

In a year with so many great contributions from black filmmakers, it is apropos that Spike Lee made one of the best films of the year. Though his last film Chi-raq had its defenders, the last dozen years of Lee’s filmography includes minor films with less-than-favorable receptions (Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, Red Hook Summer) and the inexplicable remake of South Korean masterpiece Oldboy. Over those years, Lee became something of a caricature on social media, more known for bizarre Kickstarter videos than films with any impact. BlacKkKlansman had all the makings of continuing that trend with its strange (albeit true-life) story of a black detective infiltrating a local chapter of the Klan. What makes its success all the better is that is in completely in the voice of its auteur—it is big, brash, messy, loudly screaming its messages in a way that is unpretentious and (sometimes uncomfortably) inescapable. But it also happens to be an incredibly bright, funny, entertaining undercover cop story. As the characters sink deeper into the world of the Klan, the film is able to balance derision of their philosophies while taking their threat through both violence and politics seriously. It also smartly condemns them not just through comedy, but through comparison—a cross-cut sequence between a speech by David Duke and one by a black man recounting the lynching of an innocent friend is one of the most memorable in a film with many iconic moments. The film’s finale, with documentary footage from the tragedy at Charlottesville, Virginia during protests of a white nationalist rally is reminiscent of Lee’s Malcolm X, in particular, but with a slightly different pursuit. Here, Lee ends his over-the-top comedy, one with something of a happy ending, with the realization/reminder that these human divisions are still going on. And we need to take these threats seriously.

6. You Were Never Really Here

The most interesting and unpredictable character study of the year, Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here is a brutal dive down a rabbit hole of violence and trauma. Joaquin Phoenix has long been my favorite working actor and his performance as troubled hitman Joe fits right in with what he does best. He’s enigmatic, a character completely out of control while keeping a reserved visage, I truly never knew what he would do in any moment. Ramsay knows exactly how to shoot Phoenix, utilizing both his textured face and simultaneously hardened and doughy body. In Phoenix’s best performances (The Master, Her, even the glossier Walk the Line) I find myself intently following his face, studying it. Ramsay’s quiet and contemplative tone is the perfect place for that. Stylistically, Ramsay brings an expert balance of violence and artistry, peaking with the film’s standout scene of a rotating CCTV feed capturing Joe marching through a house fitted for underage prostitution. Ramsay rarely shows violence outright, but frequently shows just enough to give the brutal implication and isn’t afraid to show the blood-soaked aftermath. The way we see Joe affected by this violence, both in the moment and as a result of it, isn’t narratively clear but begins to build naturally—quick flashbacks to his experiences in war and (from the best I can gather) the FBI and as a boy with an abusive father fill in the backstory without being expository. Above all, though, You Were Never Really Here, like the bulk of Ramsay’s work, is about a completely pervasive tone—there is enough plot there to make for a compelling story, but is a film about Joaquin Phoenix stalking down long hallways and sitting alone, covered in blood.

5. Shoplifters

Hirokazu Koreeda has built a career on small stories about family in modern Japan. Shoplifters continues this narrative trend in a wacky sort of way, following a chosen family of mismatched misfits who have arrived together by unusual circumstances. Koreeda builds these characters with so much care, I couldn’t help but love them even though, at the end of the day, their matriarch and patriarch aren’t exactly model citizens. The film smartly plays their minor shoplifting crimes with whimsy, allowing the viewer to dip their toes into their criminal behavior before exploring their more difficult actions. Even the central premise of “adopting” a young abused girl isn’t done in a way to condemn the characters, who sort of get caught up in it while wanting to do the right thing in their minds. That is until the brilliant third act shift where everything begins to fall apart. The point-of-view shifts from the family to the authorities and the media, and they aren’t so forgiving of their way of life. This really complicates the film, further examining justifications for their actions with the interrogation of matriarch Nobuyo (played wonderfully in these final scenes by Sakura Andô). Even in the end, the small moments shared with these misfits are well worth it—the enjoyment of croquettes, the day at the beach, running through the rain, a sexy afternoon with the kids away, and, of course, the adventures in shoplifting. Shoplifters may be about characters who aren’t inherently likeable, but with Koreeda’s humanist storytelling style, I can’t help but love them.

4. Blindspotting

Oakland, California had a big year on film in 2018. Ryan Coogler brought the biggest superhero film of the year there, it was the perfect setting for Boot Riley’s insane satire Sorry to Bother You, but Blindspotting proved to be the clearest and most exciting profile of the changing American city. Right at the start, in a very creative opening title sequence, we see the theme of two converging Oaklands. A split-screen montage shows off the black and white cultures in the city: images like a row of townhouses set across a homeless population living under an overpass, a corner grocery store set across a Whole Foods, young black men skateboarding set across a young white man balancing on a tightrope in a park, etc. The images come through so quickly that it works more subtly than my description would probably suggest. Writers and stars Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal tell the story of their city through another of 2018’s major tropes, the killing of an unarmed black man by white police, and first time filmmaker Carlos López Estrada tells that nearly oversaturated story with a striking visual style. There is both a looseness and intensity in the way the film moves, making Blindspotting one of the clearest voices on the social issues and also broadly funny. Diggs and Casal are natural performers together, with amazing on-screen chemistry, and both are genuine stars in their own right. Diggs has already made his name with his success in Broadway’s Hamilton (he has another opportunity to show off his rhyme skills), while Casal is completely authentic in a role that shouldn’t necessarily work so well. I didn’t expect Blindspotting to be a film where I genuinely wanted to hang out with the characters, nor did I think it would be one of the most dynamically entertaining films of the year.

3. The Rider

Using “real people” to tell a fictionalized story set in their world is a well-worn cinematic device, even a signature style in major international cinema movements. In that way, Chloé Zhao’s The Rider isn’t unique. It might be, however, the best blend of documentary and fiction, use of non-actors to tell the story of their community, I’ve ever seen. In a way, the core of The Rider is about the death of one man’s old west ideal after injury takes away his ability to ride. Brady Jandreau gives one of the year’s most compelling and heartbreaking performances and shows genuine star power. The film’s approach makes it easier for Jandreau, though, as many of the film’s best moments are when the story takes a step back to watch him in his natural environment training horses, though there are plenty of interactions with his family or scenes like a brief interlude on a temporary job at a grocery store that build the character through the narrative. His relationship with friend and mentor, Lane Scott, is obviously a highlight. The first time Lane appears (after dialogue has established who he is and that he had a serious accident) is completely devastating, but his scenes with Brady progressively showcase their heart and perseverance. Telling this story essentially as narrative fiction should come off as exploitative. It doesn’t because Zhao clearly respects these people and lets them craft their characters on their own terms. Through Zhao’s eye, The Rider is incredibly inviting and warm, despite the pervasive melancholy tone and building realization that there are no happy endings for a cowboy.

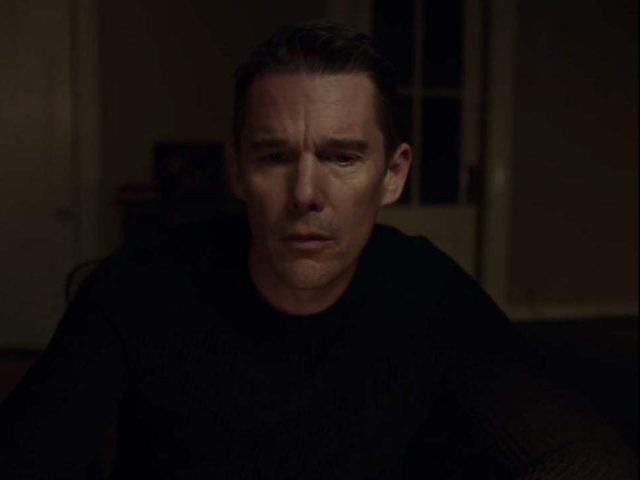

2. First Reformed

As a film student, I admired the work of Robert Bresson, especially Diary of a Country Priest, but its coldness left me removed. I could appreciate it on an artistic level, just couldn’t connect on an emotional one. I’m not sure if it is because I’m older, with a baby, or the modern setting with modern issues on its mind, but the transcendental quality of First Reformed hit me deeply. There hasn’t been a film in 2018 that I’ve thought about, wrestled with more. Reverend Toller (Ethan Hawke) is the perfect character conduit to spark this connection—inquisitive, open, passionate, troubled, spartan. Hawke delivers a powerhouse performance of intense stillness, one of the best of his career and an example of his maturity as he’s become an older actor. The film’s plot kicks off with an exhilarating argument between Toller and a young man who wonders if God can forgive man for how we’ve treated our Earth. It is one of the best examples of two opposing viewpoints coming to understand each other through debate. As someone who has worked on environmental issues and is an atheist, I should naturally come on the side of Michael; however, the balance of the dialogue between science and faith is extraordinary and seeing the film through Toller’s point-of-view doesn’t heighten or diminish either side. From there, First Reformed pulses with energy and dread. It goes places I didn’t expect, though with a clear progression through Toller’s personal crisis journey. Even with two viewings, I’m not exactly sure what to make of the ending, but the perfect build to that point gives me trust in what writer-director Paul Schrader is going for, so even if it doesn’t exactly click, it leaves an impression.

1. Leave No Trace

If you hear the basic plot of Debra Granik’s Leave No Trace, I assume you’ll have some immediate impressions. A story about a father, suffering from PTSD, and his teenage daughter living in the wilderness is surely going to be a tough, emotional sit. When they are inevitably found out, the system would surely chew them up and spit them out, not understanding their needs or way of life. Encountered strangers would surely take advantage of them in their vulnerable situation. But Leave No Trace doesn’t turn to these easy narratives. Instead, it is actually incredibly life-affirming. The system, ultimately, isn’t perfect, but it wholeheartedly tries to provide a healthy alternative to their lifestyle; the strangers along the way are open to help in any way they can, showing incredible understanding and kindness. Will and Tom’s journey is full of challenges, of course (most of them come from their own self-destructive tendencies), and there are plenty of devastating emotional moments, but it never turns into melodrama. There are no villains though there certainly could be—and probably would be in reality—Leave No Trace doesn’t need them to tell its rich, emotional character driven story. There is also an incredible economy in the storytelling, especially in the opening and closing moments. The film starts with Will and Tom living in a national park outside of Portland, Oregon, setting up their routines, how they think about the world. On my second watch of the film, I misremembered this section taking up so much more time, a testament to Granik and the actors’ abilities to build these characters and make their strange circumstances easy to understand. Without completely knowing these people, none of the drama throughout the film works—Will’s need for this independence would come off cheaply and there would be no stakes to keep him and his daughter together. By the end, this pays off exceptionally well in one of the most emotionally complex scenes of the year, one that isn’t “happily ever after” exactly but is a moment of character development for the young protagonist. Will and Tom’s mutual decision at the end of Leave No Trace is so easy to buy and despite being a seismic shift in their lives, completely right.

Overall your list was good (with the exception of Paddington 2 – all the films

in 2018 and you insert that into the best 10?)

1)

However, the grammar in your first sentence is awkward, caught my eye,

and made me stop reading in order to make sense of why it sounded

awkward.

You wrote:

“It just isn’t fair to pick only 10 films to represent the best of

2018—this is a year that could easily warranted a Top 20.”

Since your statement alludes to something that was possible but did not happen

the modal verb form of “could have” should be used rather than “could” alone.

“Could have” implies that something was possible (e.g., a top 20 was possible but

was not chosen). “Could easily warranted” does not sound right. Read or say it to

yourself.

https://www.perfect-english-grammar.com/modal-verbs-of-ability.html

2)

In the second sentence you mixed verb tenses and make another awkward sounding

statement.

You wrote:

“In fact, I could completely rearrange this list, including 10 different titles…”

It reads and sounds much better like this:

“In fact, I could completely rearrange this list, include 10 different titles…”

3)

In your third sentence you wrote:

“…I actually wrote up for more than ten,”

You don’t need that “for” inserted in there, or

a rephrasing such as “wrote down” or “listed” would have

been better.