Criterion Prediction #218: Raging Bull, by Alexander Miller

Title: Raging Bull

Year: 1980

Director: Martin Scorsese

Cast: Robert De Niro, Cathy Moriarty, Joe Pesci, Theresa Saldana, Frank Vincent

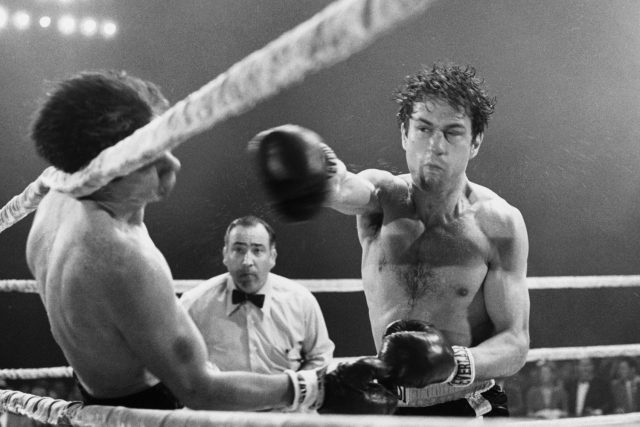

Synopsis: The career and life of boxer Jake LaMotta is chronicled over two decades; if his mercurial temper isn’t dictating his matches in the ring, it’s also relentlessly testing the patience of his friends and family. While that temper helps dish out animalistic clobberings of his opponents, however, LaMotta’s abusive tendencies extend to everyone around him, alienating his friends and family.

Critique: The “perfect” movie doesn’t exist. I know that comment is problematic and can potentially ignite a litany of rebuttal but let’s forego that conundrum. However, some movies feel about as close to perfect as can be and, like so many films by Scorsese, Raging Bull is one of those. Scorsese is on one of those trips that come to the truest screen artists and at this time he’s working at his collaborative apex and he seems to be hitting every note with naturalistic ease. This spell extends to the cast and crew. De Niro is at his transformative best, Pesci is casually engaging and the third, equally important player, Cathy Moriarty, seems plucked from the film’s period. Vikki LaMotta feels like she is from NYC’s mid-century neighborhoods and, with each narrative ascension, she inhabits her new role of wife, mother, then divorcee, calloused from emotional and physical abuse as well as mental strain. Like so many steadfast women suffocated by toxic masculinity, Moriarty’s presence becomes a vital counterpoint.

Raging Bull is one of those movies brimming with “firsts.” It’s the first aesthetically restrained but artistically succulent chronicle of a flawed, lesser-known subject. Scorsese’s objective gaze is the benchmark of what would follow with detached, documentary-esque semi-fictionalized biographies. Foxcatcher, The Wrestler, The Fighter; it’s not just sport that unites them, it’s the icy commitment and the commitment to historical, narrative and filmic construct. While De Niro isn’t the first actor to fully immersive himself into a role (nor is this the first time for De Niro to do so either), his performance as Jake LaMotta is one of rugged application. It’s not just the weight gain and the devolution from cut athlete to the slovenly deviant. He’s mainlining that animalistic mentality as well. De Niro channels the truly reprehensible characteristics in broad strokes (beating his wife and brother) then driving home the roiling nastiness of LaMotta with more specific moments later in the film. De Niro’s wheezy, neanderthal final act paints LaMotta with shades sadder than we’ve seen in a Scorsese movie. His nightclub act is merely a cipher of regurgitated, tough guy quips; he’s posturing as this seething, rotund poet. Still, his audience is captive in that they see another brutal performance but, without an opponent, the self-directed pugilism is all that’s left. He talks to his guests and we see they don’t really like the parlay of dialogue outside a perverse curiosity. LaMotta’s syrupy comportment, awkward social cues and bold entitlement almost push him into the realm of the pitiable. But then his trysts with teenage patrons swiftly dash that glimmer of potential sympathy. Afterward, in 1958, Jake is back behind the microphone and it doesn’t seem like he’s learned much. He’s baiting his audience, mouthing off. When he bellows out, “Pop, you’re going to force me to make a comeback,” it doesn’t read so much like a joke as it sounds like Jake wants to beat the shit out of him. But he won’t because we know and he knows that he won’t win.

Prior to Goodfellas, Scorsese wasn’t the go-to director for gangster movies. In 1980, people weren’t clamoring for “that Scorsese touch,” ergo voiceovers, fast editing and an onslaught of music cues mired in a world of crime. Raging Bull has the Catholic baggage commonly associated with the director’s work but this time around he’s working closely attuned with the brawny interiority of De Niro and the weighty tie-ins concerning themes like the body as the temple and the lumbering, blind path to redemption. It resonates with a unique power that feels like a form of catharsis that only Scorsese could evoke.

Why It Belongs in the Collection: There are plenty of qualifiers for Raging Bull’s inauguration into The Criterion Collection; for starters, it’s a brilliant and majorly important film in American cinema. Secondly, Scorsese’s profile in The Criterion Collection (which has always been rather high) seems to be rising. Rumors of another World Cinema Project are in the works. He continues to restore elusive arthouse films and curate titles as well. Lastly, Raging Bull was a gem from Criterion’s LaserDisc days. Of course, not all of their Laserdisc titles are due for a comeback. Still, we’ve seen a few with The Big Chill, Tootsie, The Princess Bride, The Magnificent Ambersons, and sex, lies and videotape.

“documentary-esque semi-fictionalized biographies […] The Wrestler”

I thought that was entirely fictionalized, with no documentary aspect.

“Documentary-esque” is just another way to say “cinema verite” or in the mold of realism