Cryptozoo: Joe Exotic’s Lonely Hearts Club Zoo, by Dayne Linford

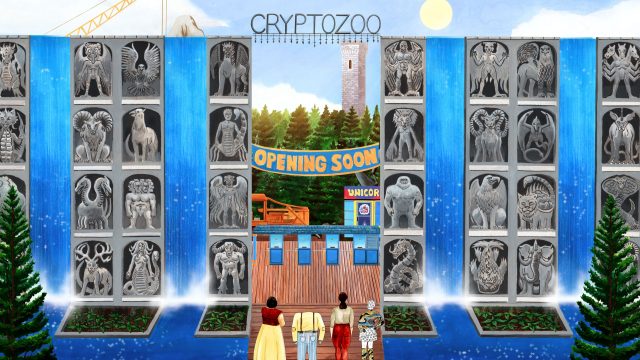

Long before Tiger King hawked his exotic wares in a country with more captive domestic tigers than exist in the wild, the zoo itself was created to service the imperial tastes of European kings eager to flaunt their reach with real specimens from faraway lands. The Tower of London, infamous as a vertical torture chamber where out of favor royalty went to die, was also a zoo, keeping lions, an elephant, and a polar bear in cramped, equally grim conditions. Londoners flocked to see these strange creatures, perhaps in the same way reporters swarmed to see Bigfoot in a freezer, the way people might come to the zoo imagined in Cryptozoo, written and directed by Dash Shaw, in his follow up to My Entire High School Sinking into the Sea. Just outside San Francisco in the boho mid-60s, aged heiress Joan (Grace Zabriskie) has built a massive, Epcot-esque complex featuring cryptids, creatures from mythology and folklore, captured around the world, presumably to keep them safe from a thriving, exploitative black market and the pursuits of the American government. Her best captor and self-styled liberator, Lauren Gray (Lake Bell), has recently gained a line on a powerful cryptid, the Japanese Baku, setting off to “save” it before the abnormally crass Nicholas (Thomas Jay Ryan) can snatch it for the U.S. military industrial complex.

A fresh, heady mixture of Art Nouveau printmaking, Tarot, Albretch Duhrer and Prince Valiant, all deliberately flattened against splashes of tie dye pastels, the animation is exceptional and derived directly from the setting and subject matter. Each of these elements contribute to a strong formal style, entirely original to the film. Animation Director Jane Samborski, who shares the film’s top credit with Shaw, layers this original style into the filmmaking with conventions and techniques particular to animation as a form, most notably in a Tarot reading scene. The cards move without hands as the card reader explains their functions and meanings, taking on narrative momentum for themselves beyond human agency, expressively building urgency as the room literally tightens around our characters. This drive to animate in new ways, however, sometimes distracts from the already powerful cinematic tools available, slowing the pace or confusing delivery. Though daring and skilful, the tendency of Cryptozoo to go for broke when it could say more by doing less sometimes leaves the animation ill-footed.

When the animation stumbles, other elements that don’t quite measure up become all the more glaring. The dialogue is expository and declarative, characters routinely offering up the rules of various cryptids before laying out the function of this particular scene and the truths about themselves and each other with unerring accuracy. Distinguished more by accent than syntax or habit, the characters themselves are lacking. Lauren leads the film with a leaden weight-of-the-world mein, having no texture beyond her stated obligations, while Nicholas opposes her with even less – he is only a caricature, big, dumb, and obvious. Joan, offscreen most of the film, is the most defined of the leads, but her potential weaknesses and assumptions, though they may be deadly, are left unexamined. She is simply a dreamer. Even active cryptids like Phoebe (Angeliki Papoulia), a gorgon who tranquilizes her snake hairs and wears contacts to keep from petrifying people, are ultimately defined by their victimization, let alone those lacking human intelligence. These may have three heads, but they stampede like panicked elephants, and die in the sad, noble ways megafauna have died on screen for decades. With so many different cryptids, often barely even cameos, individual characterization becomes difficult. Creatures from 19th century adventure novels, misrendered real animals, fairy tales, mythological monsters, and urban legends are packed shoulder to shoulder at the zoo or run amok, the sheer variety and number of them confounding any firm idea of the nature of their lives or personalities.

The Baku, who eats dreams, sets the stakes of the film, but also the limitations of its conception. At the height of the Cold War and the American peace movement, the U.S. government is apparently hunting the Baku “to wipe out the dreams of the counterculture”, as if it was ever really a threat. The conflict, between peace-loving zookeepers and uber-violent would-be fascists, is so broad and self-serving it erases potential subtler choices made in the film. Ending with the declaration that “we needed them more than they needed us” provides a soft critique of the utopian visions both of the young hippies who actually bring this all crashing down and of Lauren and Joan themselves, but the macho, cartoonishly violent Nicholas and the cryptid black market leavens that weight entirely. These comparisons render the zoo, while acknowledging humiliation, as the best possible solution to the ongoing abuse of cryptids by humans. An actual, historical comparison, however, recalls similar utopian self-aggrandizement in the World’s Fairs of a century ago, featuring as a main attraction zoos of their own, caged displays of “primitive man”, kidnapped from faraway places. The long film history of using fantastical creatures as some kind of analogue for human diversity and cruelty is spotty at best, but certain choices here make this real world corollary appalling. Some of the keepers at Cryptozoo are pursuing sexual relations with their caged cryptids, an arrangment that calls to mind both the rape of slaves in U.S. history and the modern comparisons of queer and interracial relationships to beastiality. Instead of dark commentary on utopia as actually practiced in human history, however, here these coercive relationships are romantic, maybe even ideal. This angle makes the film self-contradictory at best, offensive at worst, and just another in a similarly long history of liberal films betraying deeply illiberal assumptions and perspectives.

Though imaginative, often beautifully striking, the ambitions of the film’s aims undercut themselves. Like the number of cryptids, the sheer volume of real-world metaphors left optional simply dilutes any interesting single take, an attempt to include all possibilities meaning that all lack equally in impact or depth. In some ways, Cryptozoo knows this. After all, it’s the two post-coital hippies aimlessly wandering the woods whose dreams introduce the utopian hopes of the film and whose mistakes, upon finding the zoo, end up destroying it. But the first red flag for me wasn’t the pointless death of a cryptid, it was the dream itself, where all the hippies gathered in Washington D.C., protesting the war and the government, before they stormed the Capitol and seized power for themselves. Discussing their utopian chimera, the hippies agree it was a wonderful dream, but these days, it might strike with a different resonance.