David’s Movie Journal 1/4/12

As you may have noticed, there have been a lot of lists popping up, as is always the case at this time of year. Tyler and I won’t be doing our list until the week before the Oscars, per tradition, because as part-time critics, we need to do some catching up. So the next few movie journals I do will likely be concerned chiefly with movies from 2011 that I need to see.

The Descendants

Alexander Payne keeps heading west. After his “Omaha trilogy” (Citizen Ruth, Election, About Schmidt), he took his often intriguingly passionless explorations of white, middle-age, bourgeois ennui to California with 2004’s Sideways. Now, with The Descendants, he’s gone about as far as the boundaries of the United States will let him, to Hawaii.

I’ve always been drawn to Payne’s brand of gentle misanthropy. Buried beneath the “indie” comedy that is edgy by your parents’ standards, there’s a cold pragmatism to his work that often crosses over into actual mean-spiritedness. The Descendants has plenty of that but in other ways Payne is out of his element here, and not simply because he’s off the mainland.

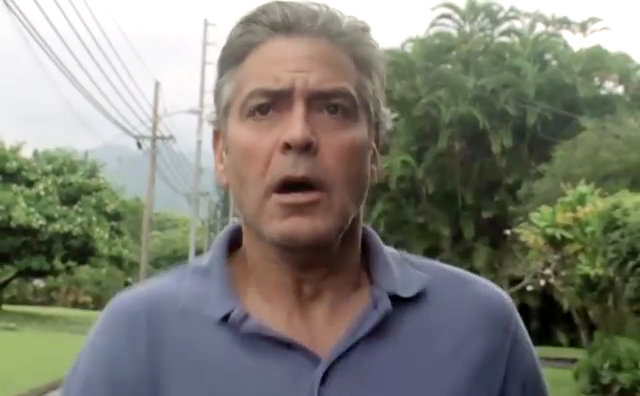

For the first time, Payne is telling the story of a man who is currently and actively a parent of children. Jack Nicholson’s widower in About Schmidt is the closest he’s come before – and there are numerous similarities between that film and this one – but that man was the all but estranged father of an adult. George Clooney’s Matt King is left the direct responsibility of his two young daughters when his wife enters a coma after a boating accident. Meanwhile, Matt’s extended family is deciding what to do with the grotesquely lucrative plot of land into the custody of which they all happened to be born. These two storylines will continue and eventually merge to illustrate Matt’s journey toward learning to be present and to focus on what’s important to him and his family. It is, to borrow a phrase from Jonathan Rosenbaum, “lightweight uplift” but it’s handled deftly from a thematic and intellectual standpoint. Along the way, though, Payne struggles to effectively portray any believable relationship between Matt and his girls. This is not a man who hasn’t had anything to do with his daughters’ life in years, like Nicholson in Schmidt. Matt lives in the same house as these two young people yet at times it feels like they’ve just met. It’s hard to accept that this man even existed before the movie started.

Still, there are things to enjoy about The Descendants, chiefly in the performances. The long-underrated and underused Mathew Lillard is subtle, realistic and funny as the man Matt’s wife was having an affair with before her accident. Veterans Robert Forster and Beau Bridges oscillate between warm and threatening in ways that are a delight to behold. And young Shailene Woodley, already with a bounty of television work under her belt, announces her cinematic presence with a performance that is the definition of commanding.

Also and as always, there is Payne’s cruel sense of humor. There’s a scene near the end where Clooney and Judy Greer face off over the comatose body of Matt’s wife that is sickly hilarious and achingly uncomfortable. In fact, a lot of what happens at the end of The Descendants is rather impressive. It’s just too bad it was such a slog getting there.

Melancholia

Speaking of dark senses of humor, Lars von Trier – brilliant though he may be – has often tripped himself up by reaching too far for an offensive joke. That’s the case both in his films and in real life, as you’ll recall from this year’s Cannes film festival. Yet the humor in Melancholia – and there is more than you’d think, particularly in the film’s first half – is surprisingly crowd-pleasing and old-fashioned. The laughs come mostly from repeated silent behaviors by certain people – the butler, the wedding planner, the young new coworker to Kirsten Dunst’s character. One bit, however, in which Stellan Skarsgård throws down a plate of food and marches off, only to stomp back into frame after realizing the plate didn’t break and finishing the job before stomping off again, is truly inspired.

All this levity is the backdrop to Dunst’s Claire, on her wedding day, slipping gradually but inevitably into a grave depression. The second half of the story takes place an unstated number of days later (probably about a week) at the same expansive estate that hosted the wedding. That property belongs to Claire’s sister, Justine (Charlotte Gainsbourg), and her husband, John (Kiefer Sutherland). Dunst, Gainsbourg and Sutherland inhabit most of the film and each are doing some of the best work of her or his career.

Despite the absolute necessity of the first half, it’s the second half with which I really connected. Von Trier’s quieter, less populated scenes allow for the powerful moments to resonate, such as a heartbreaking sequence wherein Claire becomes angry with her favorite horse (which is nowhere near as ridiculous as that sounds). The tension there, and in the other scenes in the latter half of the film, is spawned in large part by the discovery of a giant rogue planet called Melancholia, which is hurtling through space and may crash into Earth, destroying our world and killing everyone and everything on it. The metaphor for the crushing helplessness of depression is unsubtle but viscerally impactful. After seeing this film, I may not have been happy but I was moved, maybe even transformed.

That first half, though, which is starkly un-surefooted compared to the elegant hour that follows it, will keep me from proclaiming this one of the best films of the year. Also nagging are some science fiction questions that don’t seem to have occurred to von Trier at all. Is – or was – there life on Melancholia? What effect does a gigantic planet careening through our solar system have on the orbits of other planets, whether it hits them or not? That the air goes thin when Melancholia is near Earth because it’s “stealing our atmosphere” is another worthwhile metaphorical touch but what other changes would we undergo? Again, these are minor distractions in the big picture but, then again, the melancholic are given to pondering.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In was, and remains, a singular work of beauty. Having seen it, I both was and in other ways wasn’t prepared for the director’s outstanding English language debut, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, based on John le Carré’s 1974 novel.

Part of the wonder of Let the Right One In was that Alfredson punctuated his subdued and gloomy Scandinavian atmosphere with scenes of unabashed pulp excitement. B-movie scenes of action and gore were integrated seamlessly into his art-house meditation. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is less obvious ground for such tricks than a vampire movie but I quickly started recognizing those tendencies when Alfredson would linger on a fresh bullet wound or a slit throat. What took me by surprise, though, is how deftly the director has adapted to another genre. I don’t mean that he’s proven himself a journeyman; far from it. I mean that he understands the spy movie as well as he understood the horror movie and has an equal amount of success both reinforcing and subverting the expectations they bring.

There may not be many overt similarities between a scene in Let the Right One In where a man’s face is melted by hydrochloric acid and a scene in Tinker Tailor where two spies have a secretive conversation on an airport tarmac while a small plane lands behind them and taxis dangerously close. Yet both are examples of Alfredson’s affinity for exaggerated flourishes that aren’t quiet necessary but remain in the memory long after the fact.

So far, I’ve discussed Alfredson’s last two films in terms of their similarities. Truly, though – and despite the lasting merit of Let the Right One In – I believe Tinker Tailor is yet an improvement for the filmmaker. There is a structural freedom to the work that can only come from someone who expertly understands and respects the structure from which he has freed himself. He is not tied down to the beats that a spy movie – or a movie in general – is supposed to hit. This makes, at times, for a confusing film (intriguingly, not frustratingly, so) but if you’ll only trust him, he’ll deliver on everything by the end. He very much does so but the trip there has been unlike most of what you’re used to seeing. It’s not a straightforward narrative but it’s also not like other such sprawling films – Stephen Gaghan’s Syriana, for instance – that consist of tiny pieces adding up to a whole. Alfredson’s film is rather composed like a long piece of music. Its theme keeps it chugging along but it will occasionally touch down for extended movements; stories within the story. Here, we may spend ten minutes with Tom Hardy’s character and his recent adventures abroad. And then here we spend another length of time with Benedict Cumberbatch’s spy as he steals secret documents from his own employer. Each segment has its own cadence and feel but each is also an integral part of the entirety.

Above, I used the word “singular” to describe Let the Right One In. That applies to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy as well. And I don’t mean to be hasty but at this rate, it could ultimately apply to Alfredson’s career.