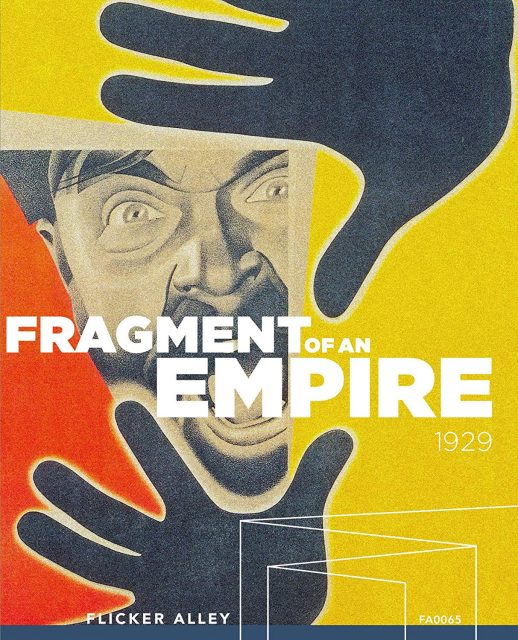

Home Video Hovel: Fragment of an Empire, by David Bax

With every film from the era that I watch, I become increasingly convinced that the late 1920s represented a peak in the cinematic art form. Like many of these films that I’ve seen in recent years, I watched Fridrikh Ermler’s Fragment of an Empire thanks to a new Blu-ray release by Flicker Alley. Based on the evidence of this movie, at least, Ermler is a shamefully underrated artist of the bountiful early Soviet years. Here, he uses techniques like extra low angle shots over a decade before Orson Welles did. And his homoerotic montage of manly men at work arrived a full 70 years before Claire Denis made Beau travail. Meanwhile, the ghostly effect of the camera cranking at variable speeds and the use of striking minimalism–like a nighttime battlefield demarcated by a single strip of moonlight bisecting the frame–make an argument, just like so many of the film’s contemporaries do, that maybe we never even needed sound.

Fyodor Nikitin stars as Filiminov, a soldier who loses his memory in an explosion during World War I and spends twelve years working on a farm, not knowing who he is. One day, another traumatic event brings all his memories rushing back to him and he leaves the farm for St. Petersburg to find his wife. Suddenly, he is a new man in a homeland he doesn’t recognize, a full decade after the events of October 1917. If you’re wondering how he’ll adjust to this new world, I’ll remind you that Soviet film of the era was produced by and for the glorification of the state. But Ermler is too sophisticated and empathetic to make superficial propaganda. By delving into Filiminov’s fractured, conflicted mind and heart (intertitles often represent the tortured hero’s inner monologue), Ermler makes his film’s ultimate conclusions more persuasive on an emotional and psychological level.

Fragment‘s crushing opening sequence, in which a young man near death looks for refuge on the farm where Filiminov works, is almost overwhelmingly pathos-driven. Ermler’s camera stares into the boy’s face and into that of the dog who lives in the barn, spurring something past sympathy, almost like imprinting. Yet Fragment runs at other speeds than melodrama. Soon, such shots–close-ups and inserts–will be incorporated into impressionistic montages that are lively even as Nikitin embodies a seemingly endless melancholy.

He has plenty to be sad about. It’s not just that he’s lost so much of his life. In a larger, more communal sense, he’s sad to realize that, despite the great efforts of the revolution, evil still exists in Russia. Fragment of an Empire‘s ultimate argument is that, while Filiminov may have missed the revolution, the real tragedy is that some of those who did not are nevertheless living in the past.

Fragment of an Empire was restored by EYE Filmmuseum, Gosfilmofond of Russia and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival from two 35MM nitrate prints. Though some title cards were recreated, the film looks surprisingly whole and fresh, especially given its lack of historical acclaim. You can also chose between an adaptation of Vladimir Deshevov’s original score or a lovely new one by Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius.

Special features include a featurette on the restoration; a commentary by film historian Peter Bagrov (who lobbied for the film’s preservation) and restorer Robert Byrne; and three essays on the film’s historical importance, its original score and the new one.