Home Video Hovel: Le petit soldat, by Scott Nye

Jean-Luc Godard’s early ambition was in fact to be a novelist, and he took that same working method and applied it to cinema. As lead actor Michel Subor notes in the supplements on this disc, Godard uses the camera like a pen, filming when inspiration struck (sometimes relentlessly, sometimes not at all) and rearranging elements at will. The actual writing was never a major priority, usually working instead with a rough outline that would inevitably change during production. Dialogue was written the day it would be shot, if it was written at all.

Naturally, the result of that process is hardly something one would call “novelistic” in the traditional sense, but Le petit soldat comes close. It deploys unusually straightforward voiceover to situate the film’s perspective from the late 50s, when the action is set, to decades in the future. “The time for action has passed,” Bruno (Subor) declares. “I’m older now. The time for reflection has started.” An army deserter who fled to Geneva and fell in love with a girl (Anna Karina), only to find himself embroiled with French authorities who try to use his vulnerable position to get him to assassinate a radio host, Bruno may well be a character in a Patrick Modiano novel, mournfully recalling the worst period of his life, when he felt most alive.

Unwilling to either give into the French authorities or join the Algerian resistance, Bruno is conscripted into assassinating a resistance fighter, which he avoids. He instead redirects plots a further escape, this time with Véronica. The feeling for these types of stories usually emphasizes the sense of the walls closing in around the protagonist, tight corridors and empty streets where only their paranoia can reign. Godard, conversely, approaches this no differently than Breathless, the world entirely open, making the way it closes in on Bruno all the more unnerving and disquieting.

Ultimately, for all the effort to pitch Godard as a leftist propagandist in the decades since, the work itself bears out something else entirely. He emerges each time as an artist first, whose difficulty to either fully grasp or ideally represent his own politics, his films explore people in conflict over their own ideals. Godard is inevitably himself and cannot produce a work contrary to his nature, and he accidentally reveals his uncertainties about his rigid principles; the personal shortcomings he might view as strengths.

Nowhere is this push/pull more apparent than in Karina’s first big scene. Véronica hires Bruno to photograph her, and he badgers her with questions, hoping they will elicit emotions that would make for good pictures. The questions – where is your family from, do men on the street pester you, do you ever think about death, do you believe in freedom, will you take a shower in front of me, are you thinking about me – were not Godard’s because he wrote them, but because he didn’t write them at all. He filmed Karina walking about the apartment and asked her whatever came to mind, captured her answers, then recorded Subor asking those same questions, and married the two in the edit. Karina seems occasionally intrigued or even aroused, very often annoyed, and just as often confused as to whether she’s supposed to be answering in character, or if Godard’s questions could ever pertain to her character at all. “I said whatever came into my head,” Bruno/Godard acknowledges in voiceover, while Véronica turns away and sighs, “You’re getting on my nerves.”

Godard and Karina virtually moved in together midway through shooting, and were married less than a year after that; she, not yet 21, threw herself into a relationship that would prove tumultuous and tormenting over the next five years. It’s hard, now, not to see that on display in this scene; her unease, her eagerness to please, her delight in his attention and curiosity. It’s hard, too, to know how much Godard knew he was giving away here, how sympathetic she would seem and how domineering and predatory he comes across. Godard is often, and rightly, called out for the misogyny in his work and public statements, but as with the politics, the sexual dynamics are complicated by his reflexive aesthetic. Godard mostly keeps the camera trained on Karina, and the questions – even as they come from Bruno’s mouth – are heard mostly offscreen (so, too, are his insults in a driving scene later on). We are left then to see how she reacts, and her discomfort mirrors and encourages our own. As with the film’s torture scenes, this section provides something like a documentary view of the way men casually mistreat women they claim to love.

Though Le petit soldat has more shape than much of Godard’s work in the surrounding years, the craft of putting together the piece remains more important to him than producing a fully-realized piece. What Le petit soldat, like all Godard’s great films, lacks in traditional narrative or aesthetic form it more than regains in its immediacy of thought. To see what it might have felt like to live on the outskirts of society, you need a film that feels like it exists on those same margins, the corners of thought and barely-filtered curiosity that so interests Godard.

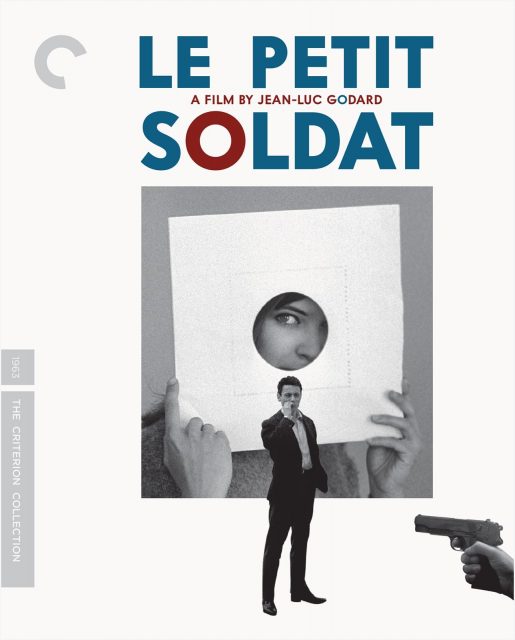

It is a great film, though unfortunately not greatly served in Criterion’s new Blu-ray. Still well worth owning for the stellar transfer, approved by cinematographer Raoul Coutard before he died in 2016, the disc is rather short on supplements, offering only the aforementioned interview with Subor, and two with Godard, all from around the time the film was made and released. The best supplement is Nicholas Elliott’s stellar essay included in a small booklet, which expertly navigates the thin line between Godard’s life and work, providing a new reading on the famed “cinema is truth 24 times per second” quote for which this film may be best known. The transfer is really rewarding though, especially for those of us who have only known the film through subpar DVD releases – this has rich, grainy texture, and exactly the sort of variety in the image density one would expect for such a loosely-produced film. The image quality dips a bit during the torture scenes, which were excised from many prints upon release, and I have to assume these are just the best extant elements. Nevertheless, though this is the thinnest edition of a Godard film Criterion has released since Alphaville over twenty years ago, it is still indispensable; especially for Godard fans, but I suspect many who find his other films too distancing will find this more classically rewarding.

Still debating if I should upgrade from my Fox Lorber DVD, I like David Sterritt’s abridged commentary though, if the transfer is as great as you say I might grab it during the next sale, thanks Scott!