Home Video Hovel- Michael, by Tyler Smith

In January 2007, my wife and I were on our way from Chicago to Los Angeles. It was a very exciting time in our lives and the move required most of our attention. However, even in the midst of all that excitement, I did manage to follow a news story about a fifteen-year-old boy that had been missing for several years and presumed dead, only to be discovered living with the middle-aged man that had abducted him years before. The boy’s parents were astonished to discover that their boy was alive, and their reunion was the initial push of the story.

It was just a matter of time, though, before everybody started to wonder about what the boy’s life in captivity was like. He clearly was not kept in a cell the whole time. For example, he had an earring, which means that he had been able to be out of the man’s house long enough to have his ear pierced. Reports came out that revealed that the boy could come and go as he pleased, but he never attempted to escape. Some pundits didn’t understand why the boy didn’t just make a run for it. That’s when the psychologists were brought in to explain that the man had such a mental stranglehold on the boy that, even at age fifteen, the boy operated under the assumption that, were he to try (and even succeed at) escaping, the man would kill him. And so the man and the boy lived together for years, almost as a sort of father and son, only much more sadistic.

I was fascinated by this heartbreaking story for years, only to discover that it is not altogether uncommon. When a child is taken, we assume that it is for a ransom, or for much more horrific reasons. But, whatever the abductor’s motivation, we assume that the child’s captivity is temporary, to be ended by freedom, arrest, or death. It is counter intuitive to think that this is going to be an ongoing crime, eventually evolving into a twisted sort of relationship between perpetrator and victim. Though it may be uncomfortable, we sometimes can’t help wondering exactly what sort of life this would be, for either party.

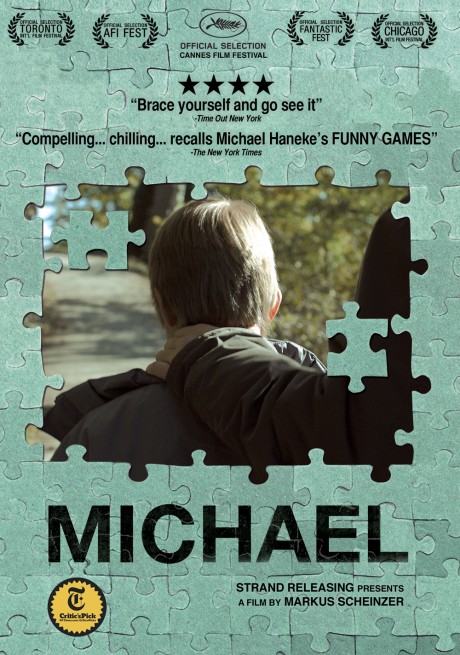

This is not easy stuff to even think about, much less depict. For that reason alone, director Markus Schleinzer deserves credit for making the film Michael, about a seemingly normal man holding a ten-year-old boy in his basement. In just considering such material, Schleinzer realizes that he has an uphill battle in front of him. The audience- not unjustifiably- will automatically approach the main character as a pure monster that we have no interest in spending time with.

But Schleizner makes a decision that, to some, may seem despicable. He tries to remain objective. There is no question in my mind that his sympathies lie with the boy and not the man (how could they not?), but he chooses instead to treat Michael as any other movie character and try to give us a portrait into the daily life of somebody engaged in truly horrendous behavior. In other words, rather than treat Michael as a monster, he prefers to see him as a person that does monstrous things. Some might say that there is no difference. I think the difference is considerable.

It is clear fairly early in the film that Michael has abducted the boy (named Wolfgang) to tend to his every sexual desire. And yet, over the years, Michael and Wolfgang develop a routine and a relationship. Wolfgang obviously does not like Michael and understands the constant threat of rape and violence, but that doesn’t stop him from playing games, exchanging gifts, and eating dinner with his captor. This defies common sense, except in that, when no other human contact is allowed, we latch on to whatever humanity we can find, even if it is within our oppressor.

Michael, too, finds himself becoming attached to the boy and struggles to keep himself aloof. On one hand, we see him take Wolfgang to a petting zoo and bring him cake to eat. We see little moments of genuine affection (I’m inclined to avoid the word “love” here). But then Michael reminds himself of what the relationship really is and turns his humanity off. For example, there is a sequence in which the boy gets sick and Michael obviously can’t take him to a doctor. Instead, he drives out into the woods and starts digging a grave; just in case.

It is this juxtaposition that makes this film so chilling. We see two characters yearning for real human relationship, but always deeply aware that this will never be it. There is a strange tragedy in this film. Though I never stopped despising Michael, it couldn’t touch how much he hated himself. This certainly does not excuse the character, but it helps the film accomplish what I believe it sets out to do: help us to understand- if only slightly- those poor, pathetic souls that defy understanding.

Perhaps that’s what makes the film so uncomfortable. It points out the common humanity between us and Michael where we thought- where we desperately hoped- none could be found.