Home Video Hovel- Plan 9 from Outer Space

It’s been said that Plan 9 from Outer Space is the worst movie ever made, and it may very well be. It’s an incompetently made film on every conceivable level. The acting is either stiff and lifeless or unnecessarily flamboyant, the dialogue unnatural and expository, the compositions designed more to accommodate the terrible set design than the actors (we’re dismissing any attempt at mise-en-scene outright), and the concept of using science fiction to address societal ills is, even in 1959, terribly dull.

And yet, Plan 9 has endured, its sheer giddiness and almost beat-poet-esque dialogue often eclipsing the technical and creative ineptitude. Some definitions of the auteur theory hold that an auteur cannot help but make a movie in a certain manner, and in that sense, there is something weirdly auteurist about Plan 9. One thinks especially of Criswell’s opening monologue (or even the involvement of Criswell, a television and radio psychic), which contains by far my favorite line of the film, “We are all interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives.” That line, like a shocking amount of the film, flies past stupid into a sort of zen state. Plan 9 is certainly a badly-made film, but its evolving reputation, which acknowledges technical incompetence while still allowing for entertainment value, has given clarity to the true nature of the film at hand.

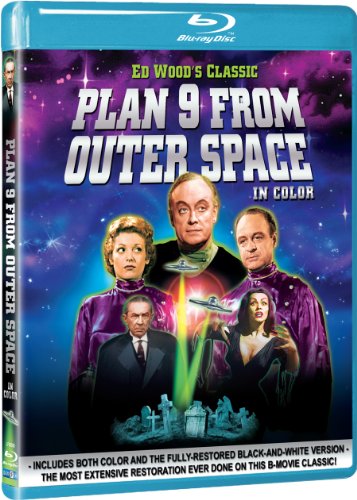

Thanks to Legend, you can now see the worst film ever made in high-definition, in both colorized and black-and-white versions. It’d be a stretch to say the transfer brings new life to the picture or anything, but I believe Legend when they say this is the most extensive restoration on the film ever endeavored, even if that’s not saying a whole lot. It maintains certain elements of a film print – flickering, a little bit of grain, nice depth – but it also looks a lot like it was transferred from video elements rather than film. Compression issues are nicely handled, but from time to time it’ll look like your DVR is trying to catch up, and you get a lot of digital noise in the process. It doesn’t happen often, and it doesn’t ruin the film or anything (honestly, what more could?), but for a film that’s been copied and transferred and encoded so many times (its public domain status ensures a long, if battered, life), they probably could have resolved these issues.

Also of note is that Plan 9, like many films of the 1950s, was shot in full-frame (1.33:1) with the intention that it’d be cropped to 1.85:1 for theatrical exhibition. Legend, however, presents it in its full-frame version, which, on one hand, they can say is the original shooting ratio, but the real reason for its presentation is twofold. First, Plan 9 gained notoriety on television, where it would have been seen in 1.33:1, and is thus the version with which people are most familiar. Second, the full-frame version has the added benefit of including many of the film’s more glaring deficiencies from a craft standpoint. Boom-mics, shadows, fill-in props, etc. would have all been covered up in its intended aspect ratio, but leaving these elements in represents, I think, a real attempt to make the film look worse than it actually is, thus propagating its status as “the worst film ever made.” It’s not a major conspiracy or anything, but given that its selling point has largely rested on that label, it’s not a surprising decision.

The audio is given a clean, if flat, presentation. There isn’t a lot of depth to the sound, due as much to the film’s production as anything else, I’m sure. Point is, you won’t have a problem hearing it, but you’re not going to buy a 5.1 system just to show it off either (that was incredibly reductive, but you get my drift).

The special features range from delightful to tedious, depending on your mood. First, the black-and-white version is considered an “extra,” even though it is, you know, the “original,” so those who give a damn would be advised to look there before pressing “play.”

“Ed Wood Home Movies,” a short batch of Super-8 movies, is kind of fun, but those without the knowledge that Wood was a cross-dresser may be a little surprised when he starts trying on some outfits made famous by Tim Burton’s biopic of the director.

“Ed Wood Commercials” is a hoot. Here we get several totally generic spots for various types of vendors that never specify the business itself (“I got these boots at my favorite men’s store!”), and in fact have a title screen at the end that just says “sponsor card,” with the intention that anyone could use them for their applicable business. In addition to men’s clothing, we get jewelry, used cars, and more.

Now for the tedious. First, I realize that I am not in any way the audience for a Mike Nelson commentary track. I never understood the appeal of his two famous ventures – Mystery Science Theater 3000 and RiffTrax – as I always figured I could sit around a make fun of movies just as easily, so what’s the point. Nevertheless, I accept that these bits are quite amusing for a great many people, so your mileage may vary wildly, but even he seemed to find the whole enterprise pretty tired. I mean, Nelson riffing on “the worst movie ever made”? What could possibly be a wilder choice?

Mr. Nye, I’ve heard you on the show and think you’re funny and smart. So it hurts when I read this: “the concept of using science fiction to address societal ills is, even in 1959, terribly dull.” Lots of room for opinion in a blue-ray review, but it’s a staggering statement in light of so many non-dull si-fi’s made with a socially allegorical intent throughout the history of film, many well after ’59. Some that pop into my head as I traipse down the mental timeline: Children of the Damned, Planet of the Apes, Andromeda Strain, Soylent Green, Blade Runner, They Live, The Matrix, Never Let Me Go.

That should have been enough for me to stop reading (though I like to read you). Then I wouldn’t have had to read a defense of using full-frame presentation as a way to nudge the badness of a movie for the sake of laughs, when full-frame presentation was not the filmmaker’s intent. Think what you want about Ed Wood, but even he deserves THAT much respect.

Honestly, I apologize like hell for that phrasing, and I sincerely retract that statement for precisely the reasons you noted. Looking at it now, it seems obviously ridiculous, but somewhere in my insomnia-fueled writing, it made some level of sense.

What I MEANT to convey is that using science fiction to address societal ills is not a terribly original concept, and Wood seems a little overly giddy at the prospect of having a message to his movie.

Thanks for pointing this out, and I hope that helps.

However, you misunderstand my intention with the question of aspect ratio, and reading it again, I can see that I could have been more clear – I wholeheartedly agree with you, and me saying “added benefit” and such was written in a snarky manner that was sadly not conveyed in the rest of that paragraph.

I will certainly try to be more clear on these and other matters in the future; as one of my college professors advised, over-explanation isn’t the worst thing.

Thanks for reading, and I appreciate the comment.

I thought for sure (or at least hoped!) it was a momentary haze.

Yeah, EW is definitely happy to insert meaning, but his thesis is never upheld by anything resembling eloquence. He should’ve taken a few more notes from Sam Fuller before loading the film mag.

So now that we’re square on those two issues, I’ll try to forget that you don’t like MST3K.