Home Video Hovel: The Bolshevik Trilogy, by David Bax

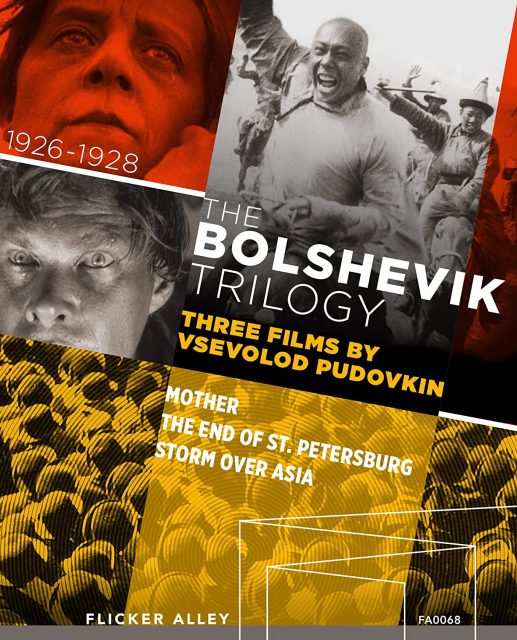

Vsevolod Pudovkin was a contemporary of Sergei Eisenstein but, while the latter’s list of notable films continues well into the sound era, Pudovkin’s legacy consists almost entire of the three consecutive works he produced from 1926 to 1928, collected in an essential new Flicker Alley Blu-ray under the grouping “The Bolshevik Trilogy.” Pudovkin actually continued directing for years after Eisenstein did (owing to having lived longer) but these three films–Mother, The End of St. Petersburg and Storm over Asia–are more than enough on their own to argue that his talents are no less worthy of consideration and praise.

Mother (1926) is set, like Battleship Potemkin, during the 1905 Russian Revolution. But, unlike Eisenstein’s landmark film, which depicts groups of Russians, from a naval crew to a whole city, struggling against Tsarist factions, Mother focuses more narrowly on one small family. In the first section, one woman (Vera Baranovskaya) sees her son, Pavel (Nikolay Batalov), and her husband (Aleksandr Chistyakov) on opposite sides of a worker’s strike that turns violent. Pavel and his fellow workers walk out of the factory only to be confronted by a group of hired thugs, including Pavel’s father. The older man is killed in the struggle and, partly through the mother’s cooperation with authorities, Pavel is sent to a prison work camp. As with the other Soviet filmmakers of the time, Pudovkin builds tension, character and sympathy through editing, be it the fast-paced fades that seem to usher contrasting forces inexorably toward conflict or the deliberately slowed down sections that anxiously await an explosion of violence. One such sequence, that of the strikers and strikebreakers facing off outside the factory, seems to anticipate the duels of American Westerns. As far as genres go, in fact, a later section of Mother has got to be one of the first prison break movies.

All of the action in Mother (and there’s plenty of it crammed into a brisk 87 minutes) is leading, of course, to the mother’s siding with the righteous forces of Bolshevism, just like the 1905 revolution led to the 1917 one dramatized in The End of St. Petersburg. The Bolshevik trilogy is undeniable propaganda but it also feels truly passionate, making it all the more persuasive. Part of Pudovkin’s talent lies in his ability to position individual characters as both audience surrogates and instructors by example. The End of St. Petersburg tells, in full, a much larger story than that of Mother. Made to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution, the 1927 film relates the buildup to the revolution, comprising years. But he still does it through the eyes of one character, a poor young man (Ivan Chuvelyov) desperate for work, like the woman in the previous film, inadvertently causes someone else’s incarceration. After going off to fight in World War I, he and his fellow soldiers come home just in time to help finish off Tsarism for good. While his comrades are dying in trenches, Pudovkin cuts back and forth between the mounting dead and the similarly improving stock market. This equation may have seemed heavy-handed a month or so ago but, at time when we see American conservative pundits actually arguing that workers should return to their jobs despite the risk of a deadly virus because it would be good for the economy, it’s all shockingly relevant. Maybe those pundits should give The End of St. Petersburg a watch to get an idea of where such lines of thinking are likely to get them. The muscular arms Pudovkin loves to showcase, after all, do not belong to those insisting, “The work day must be longer in the nation’s interest!”

Storm over Asia (1928), at nearly an hour longer than The End of St. Petersburg, is the most stodgy of the trilogy. But when it gets going, Pudovkin’s talent for capturing mass movements of frenzied violence still sears the brain. One upside to Storm over Asia‘s expanded running time is that there’s more room for moral complexity. That is, to the the extent that propaganda can allow for such a thing at all. Mother and The End of St. Petersburg mince no words about which characters are on the right side and which deserve to be crushed. In this tale of a Mongolian trader bilked by greedy capitalists who then joins the Soviet partisans fighting against the British army, there are some Brits (read: bad guys) who actually display some measure of sympathy. Meanwhile, Pudovkin addresses race, a subject left out of the previous two films, in ways that may be just as problematic and othering as the actions of the British that the film condemns. It’s all very interesting but far less immediately compelling. Until, that is, the triumphant finale in which Pudovkin uses bold and assured editing (including a scene in which he cuts back and forth between the image and intertitle, seemingly frame by frame, approaching the look of a superimposition) to suggest that revolution is not just an act of the people but of nature itself. Like all three entries in the Bolshevik trilogy, Storm over Asia may make you want to take up arms yourself and overthrow the bloated status quo.

Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray contains restoration notes for Storm over Asia (done by the fine folks at Lobster Films) but all three films are remarkably well-preserved, though Mother does have some stability issues and a loss of clarity in darker shots. Mother is available to watch localized with English intertitles while both The End of St. Petersburg and Storm over Asia contain English subtitles for the Russian intertitles. Mother has a simple but effective piano score by Antonio Coppola while the subsequent films have multi-instrumental scores by Vladimir Yurovsky and Timothy Brock, respectively.

Special features include an audio commentary on Storm over Asia by film historian Jan-Christopher Horak; an audio commentary on Mother by film historian Peter Bagrov; Pudovkin’s directorial debut, Chess Fever; a 1920 film “notebook” on St. Petersburg from a tourist perspective; a 1930 collection of images of St. Petersburg; a visual essay by Maxim Pozdorovkin; a featurette on Pudovkin’s editing techniques; and a booklet containing an essay by film historian Amy Sargeant.

There’s a Soviet “eastern”, White Sun of the Desert, in which a Red Army officer has to take on a bunch of Turkmen bandits and liberate the bandit leader’s harem. I thought it was decent enough, but I think I would have enjoyed it more if I had already read about the history of Soviet linguistic policy toward their Turkic speaking minorities (which I would have been aware of if I’d ever read “Gravity’s Rainbow”):

http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/001499.html

That sounds amazing.

– David