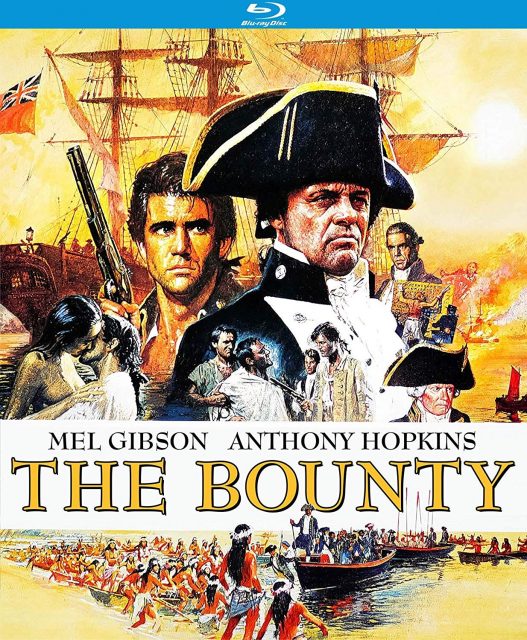

Home Video Hovel: The Bounty, by Alexander Miller

The Bounty is a unique motion picture. On the surface, it looks like your average, neo-colonialist high-seas adventure film with heaving oceans, high stakes and, given the title, a power struggle to boot. Yes, there’s all that, as well as a star-studded cast of both the old guard and the new. But director Roger Donaldson (Species, Thirteen Days) and screenwriter Robert Bolt, (who adapted the story from Richard Hough’s novel Captain Bligh and Mr. Christian) stir the pot around and, in doing so, waft away any air of familiarity that one would expect from a revised iteration of the classic Mutiny on the Bounty.

There’s a riveting undercurrent to the film that’s subtly present even from the opening credits of The Bounty that roll over a series of inspired sunset compositions while a calming but otherworldly score by Vangelis cues in. The Bounty is a rare case in revisionist historical fiction in that its revision is responsive rather than reflexive; the film isn’t a self-conscious tinkering or smug attempt to contemporize the material. The Bounty is an amalgam of stately British mores, classical dramatic structure and measured technical compositions. In addition, the contradictory nature of Victorian bureaucracy, sexual repression and colonialism come into play. While the material is reappraised with a shifting focus and dramatic emphasis, The Bounty looks both ways before crossing any streams, avoiding heavy-handedness while wielding a universally appealing sense of spectacle and awe. Initially, this film was a target for none other than David Lean, which comes as no surprise; this project falls right into Lean’s wheelhouse. I never though I’d say this but I’m glad The Bounty landed on the lap of Donaldson. Not to slight the master of epic cinema but the crux of the film’s thematic drive lies in Donaldson and Bolt’s innovative modernism.

After the credits, we’re introduced to Captain Bligh (Hopkins) at the Greenwich Naval College facing a court-martial since he lost his ship, the HMS Bounty, to a band of mutineers on their trip to Tahiti to transport breadfruit pods. Presiding over the court are Edward Fox and Laurence Olivier as the stuffy military brass. Their presence is indicative of the film’s informal representation of passing the torch from the old guard to the new. While Hopkins’ popular ascension predates the supporting cast by a few years, he almost seems to be in a class of his own as an actor and it bolsters his place as an authority figure throughout the film.

Hopkins’ characterization of Bligh is something of a thematic/contextual conduit to his crew (which is made up of a veritable Rolodex of young men who’d become iconic in subsequent years). It puts some distance between them as well. Seeing the film now, it’s a delight to see such a diverse cast share the screen. Their collective energies feed off of one another. Aboard the HMS Bounty there’s Mel Gibson, Liam Neeson, Daniel-Day Lewis, Bernard Hill and John Sessions, to name a few, and it’s no wonder that these players would become staples in contemporary cinema. Neeson has the brawny swagger of a jolly and rough seafaring man. He was not yet a recurring romantic lead and he seems right at home rigging sails and acting through his chest. Gibson’s at the height of his early game. In The Bounty he’s your proverbial colonialist dreamboat; especially after his work with Peter Weir, it almost feels like Donaldson saw Gallipoli and The Year of Living Dangerously and said: “I want him.” We sympathize with his leading of the mutiny but his performance emanates subtle conflict given his faded friendship with Bligh. Day-Lewis would hit his stride in Philip Kaufman’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being but his performance in The Bounty foreshadows the twittish Cecil he’d play in A Room With a View as well as the queer, street savvy Johnny in My Beautiful Laundrette. Hopkins is more than a one-sided tyrant. He’s vulnerable yet driven and defined by traditional naval code. He might seem like a square but there’s enough flexibility to make Bligh adversarial and sympathetic.

Structurally, The Bounty is paced as if it were a conventional adventure yarn but Donaldson and writer Bolt slyly subvert dramatic crescendos and opt for a dramatic emotional accelerant rather than one inspired by more visible action. When the crew divorce themselves from the ship to explore and eventually exploit the fruits of Tahiti, the seeds of discontent are sown. When they depart their slightly defiled paradise, the real trouble begins. Their respite is found when they bed the native women and indulge in local customs by shedding layers of clothing, donning indigenous garb, and tattoos. It’s an understated but point-blank examination of colonialism. They don’t just shirk their duties as seaman, they abandon their anglocentric values and mores. This act might seem more egregious to the crown than their actual mutiny.

The Bounty is a low-key masterpiece, an epic of consolidated atmospheric gravitas and an exercise in cultural, personal and literal exploration that is potent and yet subtle. Donaldson’s scattershot filmography is emblematic of a journeyman director but here he directs an ambitiously understated adventure yarn that has aged wonderfully and deserves to stand alongside the epic cinema of Ridley Scott or Lean and, with the presence of Mel Gibson and the synthy score of Vangelis, it’s hard not to liken the film to Weir. Kino Lorber does The Bounty more than a fair share of justice. The picture resolution flatters the beautiful compositions and sound quality is crisp. Supplementary commentaries and trailers are a fun bonus, too. It seems like this title is ripe for rediscovery.