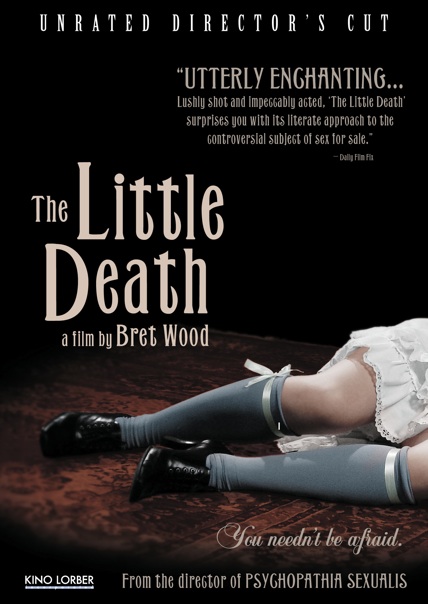

Home Video Hovel- The Little Death

I attended the same film school at which award-winning director of photography Janusz Kaminski completed his undergraduate career. Perhaps this is the reason why, despite all the things I loved about my school, there existed an annoying exceptionalism in regards to the cinematography department. The students in that concentration were, without a doubt, the rock stars of the program. As a result, the student films that I volunteered to work on as a grip or electric were generally half-baked scripts that the majority of the participants saw only as vehicles for the prettiest pictures possible. I almost never saw the completed versions of any of these films (other than fodder for shooter’s reels, their finished forms were mostly beside the point) but I imagine they must have looked like Bret Wood’s The Little Death.

Given that the title of the film is taken from the French “la petite mort,” a euphemism for an orgasm, it makes sense that the film’s action would take place in a brothel. The fact that the year is somewhere around 1900 means this is one of those classy, old brothels, which gives the makers free reign to lay on the costumes and production design. There are two simple, slightly intertwined stories being told here. In one, a woman named Eleanor Malchus (Courtney Patterson), a noted crusader against prostitution, comes to the establishment looking to free a certain young woman. Instead, she spends most of the film in the office of the owner, named Casti-Piani (Daniel May), as they argue their opposing viewpoints on what goes on inside the building. At the same time, a nervous young man named Cyril (Clifton Guterman), brought to the house of ill repute by friends, has trouble connecting with the women and mostly sits in the parlor and stews. Until, that is, he strikes up a conversation – and then an arrangement – with a woman (Christie Vozniak) who may be the one for whom Eleanor has come looking.

As mentioned above, the sets and costumes are meticulously designed and presented. The effect is actually quite captivating. The rich and lush textures and layers allow the eye to seemingly penetrate deeper into the frame. Also, it gives you something to distract from the blunt dialogue and flat acting. Returning to the issue of cinematography, however, the aesthetic intensity of the film embraces you and moves you along despite the inertia of the screenplay and performances. Cinematographer Chris Tsambis gives the objects and locations a visceral tangibility while always threatening to plunge the whole thing into the inky blackness that creeps around the edges of the frames.

Unfortunately, Wood insists on making more than just a formalist exercise. His film is a dissertation on the morality of sex and, as such, it’s of a simplicity that will make your eyes roll. There are two sides to the story. Either sex is intensely meaningful and spiritual and should therefore be treated with great reverence and caution or sex is earthly and instinctual and should have a place among the mundanity of everyday life and commerce.

What might have been interesting is if Wood had managed to say that, in their own ways, both sides are right. It would at least have the undeniable prestige of being the truth. Instead, A Little Death lands firmly on one side of the argument and, when it does, it does so with a sickening ineffectiveness, like a used condom that missed the trashcan.