Jason’s Top Ten of 2011

I love the movies and I love to love movies. But I’m one of those people who don’t think 2011 was anything close to a great year for movies. Not as good as 2004, 2007, or 2010. But, as in every Oscar season, it’s easy to over-correct and end up trashing on good (and even very good) movies just because they weren’t as great to me as they were to someone else.

This year, for me, those movies included The Tree of Life, Midnight in Paris, The Arbor, Meek’s Cutoff, and Certified Copy. I see their intentions and they have some merit, but I just didn’t find them as enthralling as I’d hoped to. Hugo, on the other hand, is just simply a bad movie that happened to have been made by a master of cinema. All of this, of course, happens every year and so it goes and oh well.

Looking over my Top 20-30 films, 2011 was still a good year at the movies, with moments of greatness. Here are the Top 10:

10. Take Shelter

Jeff Nichols, in his second film as writer and director, solidifies his focus on the fragility of the working class, mid-western family. The plot revolves around the violent, apocalyptic visions of its main character, Curtis (Michael Shannon), but the heart of the film is in his relationship with his wife, Samantha, played by Jessica Chastain (in her best work in a busy year). Nichols builds the tension gradually, as Curtis’ actions begin to have damaging effects on his family. Because of the scale of his visions, the big question would seem to surround their validity and its implications for his mental state, but that’s not what Nichols is driving at, here. Whether Curtis is right about the visions or not, there is severe hardship on the horizon for his family, so the big question isn’t if the storm will come, but how he’ll deal with it when it does. And the scenes that surround that singular question are tense, emotional, and quite powerful.

9. Margaret

Another writer/director’s sophomore effort – at long last – Kenneth Lonergan’s film about is one of the best coming-of-age stories in the past few years. Here is much more thoughtful version of Juno, that actually pre-dates it, too. Her adolescent Oscar win aside, I’ve never really thought much about Anna Paquin, but she is a force to be reckoned with as Lisa, a fast-talking teenager who witnesses a tragic bus accident that intensifies her transition from girl to woman. Instead of the usual detached teenage snark, Lisa is loud and aggressive and grating and selfish and petty and stubborn and naive and vulnerable. It’s a great performance of great material. Where most films content themselves with only a few fully-realized characters, Lonergan’s script has dozens, some main, some supporting, some given only a scene, but the writing is so good that we understand each character after about two sentences. I don’t know if the film would have benefited from Lonergan’s original three-hour cut, and there are a few minor things in the last act I just didn’t buy, but Margaret is a full film, filled to capacity with great scenes, characters and filmmaking. And it plays fair with adolescence, it doesn’t dismiss or idealize, it observes with grace, and it understands that, teenager or adult, friend or stranger, sometimes things just aren’t fair.

8. Drive

What a cool movie. Right? It’s an intense genre movie, with the most stoic of lead performances, and gorgeous, harrowing violence, all exalted to excellence by craftsman Nicholas Winding Refn. It’s also got songs that sing themselves over in your head for days. A valid complaint is that the movie isn’t really about all that much at the end of the day. It’s sortof about revenge, true, and there’s a buried parallel to the Driver’s childhood in there and maybe some measure of exploration of male aggression. But mostly it’s about Gosling’s unblinking gaze and the incredible outburst of rage that follow. It’s about some wonderfully choreographed car chases and the tone and feel of coolness, and fantastic supporting performances by Carey Mulligan, Bryan Cranston, and, of course, Albert Brooks. And that amazing music.

7. Sherlock Holmes – A Game of Shadows

I was a marginal fan of the first Holmes film, but and I agree wholeheartedly that this version of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s character and world is too action-packed and fast-cutting. But. Once you get past that and realize how pliable these tales are, the film’s qualities emerge for how much better they are executed here than in the first film. For instance, the action reaches absurdist heights, but also has real consequences. The fast-paced editing matches Holmes’ mental process and, in fact, expertly condenses an impressive amount of information. The interplay between Robert Downey, Jr. and Jude Law as Holmes and Watson are delightful, hilarious, and incredibly smart, as is all the writing (just consider the innumerable complexities of the plot itself!). The set-pieces are magnificently staged – especially the entire train sequence and the escape through the forest. But most of all, Holmes has a worthy adversary in Moriarty, played with unsettling stillness by Jared Harris. Without spoiling anything, their showdown at the end of the film is so downright exciting and tense particularly because it’s entirely cerebral. This is the best action film of the year.

6. Martha Marcy May Marlene

What sets Sean Durkin’s debut film apart from so many is the level of restraint he shows. A lesser film would have grounded us in an objective perspective and given us a straight line through the confusion. That would have been a big mistake and a boring film. Instead, there’s a breakout performance by Elizabeth Olsen, as Martha, a young woman readjusting to reality after running away from a cult. Her actions would be acceptable if she were a little kid – wetting herself, taking off her clothes to go swimming, walking in to her older sister’s bedroom during the middle of the night. Instead, they indicate intense levels of manipulation, indoctrination, and denial. Through boomeranging flashbacks we meet the cult’s leader, played by John Hawkes, who, like the film, is much scarier because of how un-sinister he is. The real horrors of the place emerge upon reflection, as we turn over the ungodly implications of seemingly mundane details. Has someone from the cult been sent to bring her back? Have they found her? Or is her paranoia another symptom of a trauma she won’t acknowledge? The film’s power comes from the plausibility of both possibilities and we’re left in a daze not unlike Olsen’s character’s, turning everything over and over while just trying to find the ground under our feet again.

5. Margin Call

Can you remember the last time Kevin Spacey was this all-out brilliant in a film? No. You can’t. His knack for playing the smartest person in the room often sells him short and leaves him nowhere to go, no conflict to push back against. Maybe the reason he’s so effective in J.C. Chandor’s feature debut is that Spacey is merely one smart person in a room filled with them, and in which he is not the most powerful. This is a film about the economy crisis that calls into question those who make up that economy as much as those who profit most from it. It presents no easy decisions, no clear villain, no winning strategy, no bold heroics. The great monologues abound – Spacey, Bettany, Tucci – and scene after scene heightens the tension while extending the plot and illuminating character. Margin Call feels like a play in the weight its words hold and how they demonstrate position and status and action. It is wisely contained in scale, but vast in scope.

4. We Need to Talk About Kevin (thematic spoilers)

Here is a film about a moment of isolated realization. It is not, despite what you may have heard, a movie about a bad seed, an incarnation of bottomless evil. It involves a lonely mother, played, in the year’s best female performance, by Tilda Swinton, desperately trying to move on after a tragedy from which there is no return. Her son was the perpetrator of terrible violence, and the film is a memory collage from his early infancy up until the incident. What’s fascinating is the way Ramsay draws the relationship between mother and son. He seems to intuit early on that she did not want him, still does not, and cannot fake it well enough. What role does this play in his development and how does it affect the assumption that this is an example of nature dominating nurture, when it’s the lack of nurture that hardened the nature? Or when the nature of the mother is passed down to the son? Or when in so many ways both mother and father are such miserable, piddling failures when it comes to basic parenting? I was utterly rapt during every moment of this film. Ramsay’s control over the fluidity of movement between time periods is impressive, and she is daring to extend the possibility that the aftermath of this tragedy might bring those very maternal instincts, whose decided lack helped lead to its occurrence, into natural authenticity.

3. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

There is something about how director Tomas Alfredson builds his frames that speaks to me in a way I cannot quite explain except to say that this is what a film is supposed to look like. Put more simply, I find a deep kinship with his visual sensibility, as well as his stylistic one. Here, Gary Oldman leads an impressive ensemble in this adaptation of John Le Carre’s novel, about a mole in the heart of British Intelligence and the former spy brought back to catch him. Some found the film too slight. I disagree. The fact that the expressions of emotion are muted should not be mistaken for the intensity of those feelings, themselves. For those patient and trusting enough to make it through some initial confusion, it is an enormously gratifying film, seeing all the disparate strands eventually weaving together a into a cohesive rope, and I enjoyed the way it devoted chapters to different individual spies, with Smiley at the center, pulling the strings taut.

2. The Descendants

Alexander Payne’s first film in seven years nicely folds together two of 2011’s major cinematic themes: Reflection and Parenting. George Clooney plays Matt King, a man dealing with a wife in a coma, unruly daughters, and an entire extended family who all want something from him. As he says in the film, he’s just trying to keep his head above water. Absent are the easy intelligence and charming air he usually employs, and I found I like this Clooney, too. I bought it. The scenery is beautiful, but in traditional Payne fashion, it’s mostly a strong character piece. And while the film does contain layers of bitterness and hurt and anger, I appreciated the common grace it extended to everyone from the surfer/stoner Sid to the cranky asshole of a father-in-law to the guy who slept with Matt’s wife and the supporting cast is excellent, especially Shailene Woodley as his older daughter. There’s that moment we see even in the trailer, when she finds out how bad her mother’s condition is and can’t think of what to do but try to swim away from it, fighting against the water for escape as her face contorts and her tears get lost in the pool. The way she’s blindsided by the pain – and her instinct to flee from it – were what The Descendants was about for me.

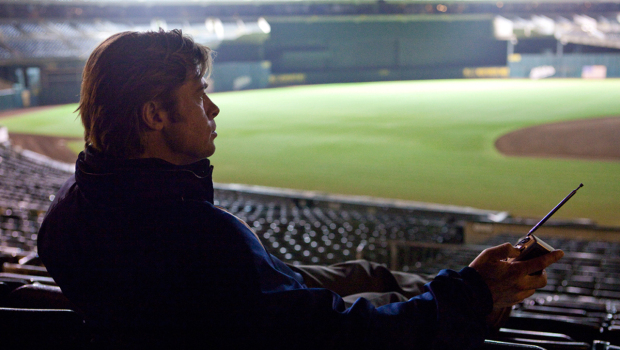

1. Moneyball

Full Disclosure: my father loves the Oakland A’s, and even though I don’t really follow baseball anymore, so do I. Aaron Sorkin’s talent has been fawned over and will continue to be as long as he writes movies with this kind of energy and intelligence. Trade deadlines shouldn’t be this exciting. And while the collective cinematic consciousness would have cut out an eye to see what Steven Soderbergh would have done with the material, and even though I don’t think this film has as clear a signature as Capote, I’ll be damned if Bennett Miller isn’t a skilled, sure director. Where did he go for six years, anyway? The unlikely pairing of Brad Pitt and Jonah Hill (both doing some of the best work of their careers) gives their scenes an interesting texture. And I loved the heaving force with which Pitt throws things in this movie, as in the scene where he makes the entire team be silent, waits, then tells them that that is what losing sounds like; and then he all-out hurls water cart out because it looked at him wrong. The talent in front of and behind camera, as well as overall authenticity of the production, which worked extensively with MLB’s folks down to the smallest details, gave Moneyball a richness and presence that most sports movies don’t even realize they could strive for. It’s such a great film. How can you not feel romantic about baseball?

Honorable Mentions:

Melancholia, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, The Trip, A Separation, The Artist, Young Adult, and Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol.

I couldn’t agree more about Take Shelter. It’s the one movie this year that got past my brain and into my gut. Anyone who’s paid attention to anything that’s happening politically, economically, socially, can see this movie for the harbinger of reckoning that it is.

I couldn’t agree with you less, though, about TTSS. I’m one of those, like most, who hates when someone derides a movie because the book or the original was better. In this case, I have to speak (after reading so many rousing reviews across the web). I saw the original 6-part BBC version before heading to the movies to see this one. The original reveals the new version for what it is: willful confusion in place of living, breathing mystery, real people in real spaces feeling real feelings and sweating real sweat instead of broad sketches moving through a spit-shined art department, and — it has to be said — actual acting instead of performance. One quick glance of Alec Guinness’s eyes tells as much if not more than a paragraph of Oldman’s hand-pocketed dialogue. Most of all, the original is a full-frontal indictment, from the first sequence on, of institutional corruption, paranoia, blithe disloyalty, where the new one seems to only use the themes as a reason to use a different filter. In comparison to the original’s final scene between Smiley and Bill in the brig, the new version is a peck on the cheek. I would never call this new version bad. It has a look, you’re right, that is easy on the eyes. But as a story, if that’s what you’re looking for, it’s deeply gutted, pocked with hobbling shortcuts, and is, ultimately, not much more than a monumental ode to style over substance. I would beg anyone who saw this movie and liked the story (and not just the bells and whistles) to rent the original BBC version.

The middle of my comment, much like the movie, got kinda garbled. But hopefully, like the movie, you still enjoyed it.

I love this list.

Here’s Emerson’s roundup of polished prose for a movie he says is the best English language film of 2011, unless I read that wrong.

http://blogs.suntimes.com/scanners/2012/02/tinker_tailor_critic_eye_some_.html#more

Reading all of it, and some of it for a second time here, I’m shamed — you should know, I’m easily shamed — because the praise makes me feel like I must’ve missed something. I’m going to see it again soon (as I did with Super 8, to give it a second chance, too, in the face of overwhelming praise [it failed twice for me]), and hopefully I’ll have a better opinion of it. Something tells me I won’t, so long as that gorgeously nimble and, for my money, more deeply *real* BBC version exists. But I’ll give it a shot.

Meanwhile, I’d love to hear more of what you liked and loved about the movie… more, that is, than just the paragraph you wrote here. I’ve had that experience of being so aligned with a visual storytelling style that I was left nearly in tears, or at the very least in a deep funk for being beaten to the punch, but unable to articulate exactly what it is that I was just so aligned WITH. These are valuable conversations to have.

Robert,

You mentioned close-ups. I thought Oldman was extremely communicative, even when he wasn’t moving a muscle. I felt like I tracked with his character throughout the entire film, even as it goes off into some other directions.

I haven’t seen the BBC series, but whether it’s great or good or whatever, this is a 135 minute version that tells a cohesive, intricate, engrossing story. All the supporting performances worked perfectly to me. This might be my favorite Mark Strong performance, I identified with his isolation completely. There are less than whispers of a relationship between his character and Colin Firth’s, and it’s handled with a very deft touch, as is the Benedict Cumberbatch character, as Smiley’s right hand man for the operation. His sequence going back into The Circus was incredibly suspenseful even in its total mundanity. It’s been called the anti-Bond, and a sequence like that solidifies the idea.

There is the entire unspoken theory about homosexuals as spies, and if you consider how controlled and specific the smallest bits of their behavior would have been at that time in their everyday lives, it makes sense that they would be quite good spies. That thread feeds into the idea of the personal wreckage in Smiley’s life in his relationship with his wife. Then you have Ricky Tarr living on the opposite side of the spectrum and all of a sudden there is a very interesting thematic connection having nothing to do with the pieces of the plot, but just as fully developed, just as intricate, and I thought Alfredson handled it all with just the right tone.

I will be boring in any back and forth on this movie — a back and forth which I started, of course. Because anything I say will always be a vis-à-vis sort of thing. I agree and enjoyed most of what you describe above (easy to track Smiley throughout, Strong’s strong performance, fun suspense via mundanity), but it all feels like artifice by comparison. I’ve been spoiled by the original, which gives you all the things you liked, but more truthfully. I’ll be forever pulled out of any deep appreciation for Alfredson’s by memory of the infinitely more fascinating people and places in the original. The ’79 rendering of Connie Sachs, for instance, is so infused with sadness, loss, regret, that the new scene can only be an affront with its titillation played for laughs.

Re: gay themes meeting Smiley’s personal wreckage. There are many connections to find and enjoy in this movie. I think it was simply not as invigorating for me to find and relish those in this version, versus watching the stories unfold around those themes and connections in the original. This is the trade off when you condense a sprawling story into a couple of hours. (BBC gave Tarr nearly a whole hour’s episode to develop.) And no one can say Alfredson didn’t achieve something by getting most of the big strokes in, and stylishly. I’m a fool to dismiss this movie for that reason. Yet there’s no escaping the comparison for me– oh… what am I doing? It’s a good movie. I’m just doddering. I’ll stop now.