Just a Regular Fellow: The Relatability of Harold Lloyd, by Tyler Smith

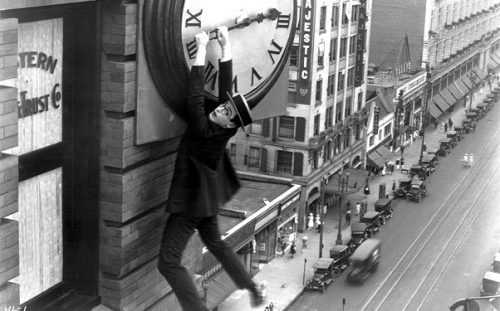

When people think of Harold Lloyd, the primary mental image is that of a bespectacled young man hanging from the face of a clock at the top of a tall building. It is a thrilling moment from Lloyd’s most thrilling film, Safety Last. However, underneath the thrills lay an important idea, and one that Lloyd would come to depend upon in his films: Relatability. While the visceral punch of his thrill pictures cannot be denied, it is the lead character’s relatability – the audience’s empathy with and recognition of his plight – that truly separates Lloyd from the other silent comedians. He accomplishes this through the use of recognizable urban settings, the design of his signature character, and his exploitation of basic narrative beats.

While an argument can be made that Buster Keaton’s stone face can allow the audience the project themselves onto him, his character remains largely impenetrable. His minimal reactions – and inability to crack even the slightest of smiles – makes him seem like something other than human; as though he is standing on the outside of human experience and studying it, rather than experiencing it for himself. Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp character, however, is the exact opposite. His character is the essence of emotion; when he laughs, it is raucous, over-the-top laughter, and when he cries, he weeps openly and without reservation. Neither of these approaches keeps the audience from fully engaging with the characters, but Harold Lloyd wanted more than that. More than mere engagement, he wanted investment. This is different than Chaplin, who seemed content to illicit sympathy from his audience, without ever tipping into empathy. And Keaton’s dry creativity was admirable, but far from empathetic. Only Lloyd wanted the audience to look at his character and see themselves. If Harold succeeds, the audience should feel as though they have succeeded.

Perhaps Lloyd’s desire for audience empathy comes from his background as an actor. While Keaton and Chaplin both started as comedic performers, Harold Lloyd wanted to be a serious, dramatic actor. His longtime collaborator, Hal Roach, said that Lloyd was never a comedian, but was instead an actor playing a comedian (Park 2013). He didn’t have an inherent comic instinct. His comedic sensibilities needed to be sharpened through years of trial-and-error, working to find the right kind of character. So, like an actor trying to figure out his character, Lloyd went to work, puzzling out what made people laugh. His Lonesome Luke character was obviously a copy of Chaplin, hidden by an appearance meant to be the exact visual opposite of the Little Tramp; clothes that were too tight rather than too loose, the ends of a mustache rather than just the middle. And while the audiences responded to Luke, it just didn’t feel right to Lloyd (Kerr 1975). Eventually, Lloyd found just the right combination of comedic elements, and for many of the same reasons an actor locks into the character he’s playing. He must see the character’s motivations and, if not completely condoning them, at least come to understand them if he’s going to convince the audience that he is that character. In other words, he must relate to the character.

Lloyd found a character that he could relate to. As a young man himself, looking to succeed in Hollywood, he was willing to do whatever he could to make it. These are the same elements that make up the Harold character; young, enthusiastic, hard- working. This kind of optimism was rooted not only in Lloyd himself, but in the era in which he lived. The Great War was ending and America was feeling hopeful and confident as it moved into the Roaring Twenties. And with Prohibition in effect, decency and goodness were the priorities (at least publicly). According to Walter Kerr in his book The Silent Clowns, “The good American… was two things: he was aggressive, and he was innocent” (1975). Harold would be both.

Along with being optimistic and hard-working, he would also be polite and upstanding, even when unapologetically ambitious. He wanted the public to see their own lives and desires on screen. This meant the character would have to be a reflection of the dominant culture. No outsized clothes, no stone face. Roger Ebert writes that Harold is “pleasant, even handsome, but not remarkable in the way that Keaton’s deadpan gaze and Chaplin’s toothbrush mustache are distinctive… [Harold in Safety Last] would have blended with the background of the department store where he worked” (2005). He was going to have to seem like any other young man walking down the street. A nice suit and a standard straw hat would be the preferred costume.

Lloyd wanted the audience to not merely see themselves as Harold. He wanted them to see the character’s weaknesses and failures, so that they might want to reach out and comfort the character. This meant achieving a certain on-screen vulnerability. And, culturally, few things create immediate perceived vulnerability and weakness as a pair of glasses. People wear glasses because they need them; their eyes are weak, so they are required to wear something else in order to function well. Glasses can break, which requires that a person be somewhat careful in the things they do, lest they lose their glasses and their visual impairment – their weakness – presents itself once again.

Lloyd’s addition of horn-rimmed glasses to his character not only makes the character seem more fragile, but more innocent. His ambition and, in some cases, aggression – two traits that do not lend themselves to a character’s likability – could be somehow forgiven because the character is seen as young and well-meaning. Lloyd commented on the impact of the glasses on the character, saying, “Someone with glasses is generally thought to be studious and an erudite person to a degree, a kind person who doesn’t fight or engage in violence, but I did, so the glasses belied my appearance” (Park 2013). In the first few appearances of the “Glasses Character”, his behavior was still no different than any other conventional Hollywood comedian; violent and aggressive, with no attempts to engage with the audience on an emotional level. It would be important to disguise certain elements of the character, as his desire to succeed could be seen in certain contexts as sociopathic. He will lie and deceive to get where he needs to go, all while seeming to the audience like a “go-getter”. Ed Park, in his essay “High-Flying Harold”, writes, “The simple pair of glasses is the uniform that renders his true nature invisible, volatile, subject to change” (2013). It should be noted, however, that while Lloyd was perfectly willing to have Harold reflect the dominant culture’s ambition, he would often couch it in the character’s desire to woo a girl and get married, as in Girl Shy (1924) and Safety Last (1923). To have this young man desire wealth and status, just to keep it for himself, would make him a bit too selfish, and even the glasses could not conceal that. Only when Lloyd softened the character up, underlining his desire to achieve more conventional definitions of success (a good job and a loving wife), did the glasses start to really emphasize the character’s decency, as well as ambition.

While Harold’s methods of achieving success could be seen as overly aggressive at times, the audience could certainly applaud his work ethic. As we see in Speedy (1928), Harold as a taxi driver will do anything for a fare. And if a potential customer initially turns him down, he persists. He is not the type to give up. The character is more than willing to put in an honest day’s work; to climb the ladder in the conventional way. In fact, in Safety Last, he literally does “climb the ladder” in the form of climbing up the side of the building. He does this to help attract attention to his place of business, for which he will get a handsome reward. His initial plan is to have somebody else do it, but when that falls through, he does it himself. As he climbs up five, six, seven stories, it gets more terrifying, but also exhilarating. This goes against many of the standard methods of silent comedic protagonists, who often attempt to avoid hard work through their own cleverness. Harold is not afraid to get his hands dirty. If he’s actually going to succeed, it’ll have to be on his own merits and with considerable amounts of elbow grease.

This kind of work ethic is something that most audiences can relate to. Most people have had to hold down jobs that they do not particularly like in order to pay the rent. Harold’s exhaustion is recognizable, but also sympathetic. When watching him deal with crazy customers and demanding bosses in Safety Last, there is a desire to see him get out of that situation, though not by simply walking out. There is no desire to see Harold quit (and, in doing so, admit defeat), but instead to rise above his circumstances through his hard work and ingenuity. This is a reflection of “The American Dream”, which theorizes that one can do anything if one simply works hard enough. And, in the postwar optimism of the 1920s, the American Dream was seen as both desirable and attainable.

Harold’s world, unlike Chaplin’s or Keaton’s, is often one of simplicity and recognizability. While the tone might be heightened, the images are not. One will not find the fanciful romanticism of Chaplin or the surrealism of Keaton. Harold lives in a world of department stores and taxi cabs, college dances and skyscrapers. It is a specifically urban world, as is fitting with the perpetual theme of American success and the pursuit of fame and fortune. Harold cannot reach his desired status in his small hometown; he’ll have to be in the middle of the action and the hustle and bustle of the big city. And it is a busy, often-stressful world that Harold inhabits. He often seems lost in a sea of people, each one in a hurry to get where they’re going. This attempt to depict the city as it truly was is decidedly different than the urban landscape as shown by Chaplin, who tended to focus on the more run-down parts of the city that the Tramp inhabits, or Keaton, whose settings were often nothing more than an extension of the story.

The camerawork in Lloyd’s films plays a big role in establishing both the scale and recognizability of Harold’s surroundings. Wide shots of the city and its citizens not only set the scene, but also the tone of the story, as in Speedy, where we are treated to shots filled with fast-moving cars and trucks. This sets up the modernity of the city, which will sit in stark contrast to the old-world sensibilities of Harold’s girlfriend’s grandfather, whose horsecar is outdated and in danger of being shut down. The incorporation of the cityscapes in this film establishes the world and the emotional stakes before we even know what they are. Lloyd shows an urban audience the world they are familiar with, only to jar them with shots of the increasingly-obsolete horsecar. While Lloyd also understands the need for close-ups, his use of wide shots underscores the enormity of what we’re seeing. Harold would not seem so small if he weren’t in such a great big world. His anonymity – the idea that he’s simply one more face in the crowd – makes him ordinary, a feeling that undoubtedly many in the audience can understand.

Lloyd’s visual choices do not merely work to establish the world and Harold’s place in it, but can also create empathy for what he is feeling. As Harold climbs the building in Safety Last, it is imperative that the danger of falling be ever present. Harold may encounter various obstacles during his climb up the building, but they are only dangerous insofar as they could cause him to fall. Walter Kerr writes, “Virtually every shot keeps the street below in view. Harold may be having trouble with pigeons that are flapping on his shoulders while he hangs by his fingernails; the street, the streetcars, the tumblebug autos, the pedestrians scurrying on their own errands are there, a sickening drop away… Even close-ups of Harold’s terror-stricken face as he clutches at a rope that is swiftly slipping through his hands are angled to show us exactly where he is and what may happen to him” (1975). While it is impossible to put the audience directly in Harold’s shoes, the film does its best to depict his mindset. The standard mantra when dealing with heights is to not look down. However, when climbing a skyscraper with no harness or safety net, Harold doesn’t need to look down to be reminded of the insanity of what he’s doing. The danger is always there for him, and the camera is used to put us in his emotional state. So, even when Harold has his eyes fixed on the wall in front of him, the camera is perpetually looking down.

Character design, camera choices, Harold himself; Lloyd utilized several filmmaking and storytelling elements to create relatability. But perhaps the primary device Lloyd employs is one that is not inherently comedic. His use of narrative to underline the humanity of the Harold character is something one would expect to find in melodrama much more than comedy. And yet, though never quite as heightened as Chaplin, Lloyd regularly told stories with emotional peaks and valleys, successes and failures, joy and sadness, all to grab the audience’s attention and keep it. Many of his stories could be borrowed from melodrama, and were rarely the stuff of comedy. But Lloyd realized that once he had an engaged audience emotionally, he could do anything he wanted with them. The thrills would seem more thrilling, the laughs more satisfying, if the audience genuinely cared about the person they were seeing on screen, and exploiting narrative elements was the best way to do that. Kerr writes, “The sympathy Lloyd learned to earn for himself was a narrative sympathy: it came from organizing the events of a film so adroitly that we had, in the end, no way of resisting what the structure was doing to us. Lloyd became so expert at tipping narrative in his favor that he could do it backward, sidewise, or head-on” (1975). Lloyd knew what audiences wanted, and he manipulated those desires to get the audience engaged. By playing so blatantly on the audience’s emotions, Lloyd would draw them into his character’s plight so fully that their investment was both automatic and enthusiastic.

Lloyd’s manipulation of the audience through narrative is on full display in Girl Shy. In the film, Harold is a young man, naive but confident. He writes a book about how to succeed with women. Though charming, Harold doesn’t seem like the type of man that would be good with women, so already his writing the book is suspicious. Nonetheless, he presents it to a publisher, eager and optimistic. A group of secretaries get their hands on it and have a good laugh at his ridiculous ideas of how to woo the opposite sex. This incorporates an important element of narrative; restricted narration. While some stories are told completely from the protagonist’s restricted narration, to the point that the audience only knows what he knows and nothing more, Lloyd chooses to let the audience be privy to information that Harold does not have. While Lloyd will often use audience anticipation for comedic purposes, he will regularly employ it to heighten the drama of the story. The secretaries hate Harold’s book, but he doesn’t know that yet; either drama or comedy will ensue. To up the emotional ante, once Harold returns, the secretaries humor him by pretending to swoon when he enters. They proclaim their love for the book, which puffs Harold up as he enters the editor’s office. The anticipation of Harold’s disappointment has effectively been both postponed and heightened, so that the eventual rejection by the editor will be all the more devastating. And the fact that the secretaries draw it out for so long – assuaging Harold’s humble assertions that surely he could not be as insightful as they are saying – cranks the emotional stakes higher and higher, until it is virtually intolerable.

This is the same principle that makes Lloyd’s thrills so effective. In the climbing sequence in Safety Last, the suspense comes from anticipating Harold’s eventual fall. With each floor he ascends, he may be closer to his goal, but that means the fall is also that much further. Later, in Girl Shy, the girl that Harold loves is about to get married. He races to stop the wedding, using various methods of transportation, each somehow more dangerous than the last. As the mad dash continues, the anticipation operates on two levels. There is the anticipation of physical disaster – Harold crashing a car – but also of emotional disaster -Harold is too late to stop the wedding. To do so addresses both Harold’s actions and motivations, which the audience has already been made acutely aware of. Just as the average audience member has a working knowledge of why they do what they do in their everyday life, seeing how Harold’s deeper desires motivate his actions creates a deeper connection between the character and the audience, and the anticipation of his success or failure is a mirror of the audience’s own fears of not achieving their goals.

The audience’s knowledge of what has happened and will likely happen to Harold plays well with the character’s youth and naivety. He does not have the benefit of 20/20 hindsight. There is only what he wants to happen and, often tragically, what he foolishly expects to happen. Kerr writes, “Without transparent self-pity, Lloyd became an architect of pity, teaching an audience to ache over what was happening – or what might happen – to this decent, if overeager kid” (1975). His is a character without life experience; everything is new and exciting. But life seldom turns out as planned, and that knowledge – and Harold’s lack of it – makes watching his eventual education painfully fascinating.

Lloyd’s use of narrative as a way to create sympathy and relatability is never more apparent than in The Freshman (1925). The story of a young man making his way through his first year of college is relatable enough to some members of the audience, but with each new plot development, the young man is brought lower and lower. He is eager for acceptance, but is ostracized. He is “the college boob”. He desires to be on the football team, but is only the waterboy, though the coach doesn’t have the heart to tell him. He hosts and pays for a party, but the attendees hate him. Like Girl Shy, Lloyd takes advantage of what the audience knows versus what Harold knows.

We first see Harold looking in the mirror, imitating his favorite movie hero, Lester Laurel. This involves doing a little jig every time he introduces himself and making the pronouncement, “I’m just a regular fellow. Step right up and call me Speedy.” Harold is excited to deploy these social tactics to become the most popular guy in school. Meanwhile, his parents gravely shake their heads. They know their son is in for a rude awakening, but the keep it to themselves; once again, the audience knows something Harold does not. Even Harold’s last name in the film – Lamb – informs the way the audience should view him; innocent, pure, and about to be led to the slaughter. Harold’s idolizing of movie character Lester Laurel is a cultural touchstone of the 1920s. Laurel is a reference to Frank Merriwell, a popular pulp character at the time, whose excellence at everything he attempted made him a cultural icon. Lloyd’s reference to this character speaks to his desire to relate to the audience at the time. Stephen Winer, in his essay “Speedy Saves the Day!”, writes, “Whether or not Lloyd himself took this archetype seriously, he recognized his audience’s appreciation of it and acknowledged its power. And so in The Freshman, the Harolds, Lloyd and Lamb, see the college hero as someone not to be mocked but to be emulated.” One of the primary ways that Harold imitates Laurel Lester is to spend his money freely, treating people and lending out cash. His fellow students are only too happy to play along, pretending to like him in exchange for free meals and hand-outs.

This all culminates in the Fall Frolic, a yearly event that Harold offers to host. He will also pay for everything. The night of the event arrives and Harold has spent a fortune on the details. However, as the party wears on, Harold’s cheap tuxedo starts to fall apart. He does everything that he can to hold it together, fearing that he might lose his fellow students’ respect. Of course, Harold doesn’t realize that he never had their respect in the first place. The audience, however, knows all too well that Harold’s attempts to keep himself together are in vain; he will never have their respect. While the tuxedo gags are amusing, Harold’s desperation is not. It is a sad thing to watch this young man – so eager to be accepted – literally fall apart. Stephen Winer writes, “Scenes like the Fall Frolic… can be pulled out of context and play just as effectively for an audience. But seeing them embedded in the film, we discover how tightly Lloyd marries his comedy to the arc of his character’s story, creating a perfect bond of laughter and recognition with his public” (2014). Just as Lloyd would accept nervous laughter from the audience during his climb in Safety Last, he is more than willing to accept the audience’s laughs of pity and recognition in The Freshman.

So many of the scenes in The Freshman feel like such an obvious attempt to elicit the audience’s sympathy, that the film could feel almost like a deconstruction of story, character arc, and pathos. Aside from Harold’s love interest, the other characters do not even have names. “The College Cad”, “The Football Coach”, “The College Hero”, and so on. Many of the key story beats feel as though they could be similarly-named. “The First Day of School”, “The Dance”, and “The Big Game”. These are certainly relatable social experiences, but here they matter primarily as how they affect poor, naive Harold; it is his story and everything else is a function of him, even though his having very little bearing on the world and people around him. This speaks to the way Lloyd was able to strip his stories down to their most essential elements. While he would allow his gags to add complexity and specificity, the story and characters are as basic and general as can be.

As is to be expected in any narrative, the events of Lloyd’s film build to a climax, when Harold must go from mild-mannered and polite to bold and strong. Ambition must eventually turn to action. In Safety Last, he climbs a building in order to secure professional and financial success for himself and his girlfriend. In Girl Shy, he embarks on a treacherous race against time to stop the woman he loves from marrying a scoundrel. In Speedy, he must outsmart and outrun a group of thugs attempting to destroy the streetcar business of his girlfriend’s grandfather. And in The Freshman, during the “Big Game”, he must rise to the challenge, come off the bench, and win it all. But it is never easy. If it were, the audience would not feel so invested. Unlike Harold Lamb’s hero in The Freshman, nothing comes easily for our protagonist. Winer writes, “It’s the irony of The Freshman that when Harold ceases trying to imitate Speedy, he actually becomes Speedy. It’s not simulated strength that wins the game, it’s Harold’s own will and tenacity.” Through hard work and ingenuity, he gains ground, inch by inch. And with each little success, he gets closer to his goal. Many audience members will be able to relate to this type of success; striving with a goal in mind and eventually achieving it, rather than simply stumbling into success or fortune.

Lloyd’s films contain a number of peaks and valleys, but always end on an optimistic, hopeful note. However, the happy ending, while unsurprising, is hardly unearned. Walter Kerr writes, “Given his transparent normality, he would have to emphasize not the ease but the difficulty he encountered in managing any situation at all” (1975). Harold has had to work for everything he has, both practically and emotionally. And, often, the biggest obstacle is his own sense of hopelessness. When Harold is in the midst of emotional despair due to his own shortcomings or failures, it’s hard for him to foresee how he will achieve his goals. But he never gives up on them; they’re always there, off in the distance, motivating him. In the same way, the audience knows that things will eventually turn out well for Harold, but it is hard to imagine exactly how. Despite the audience’s knowledge of so many things that Harold does not know, this is where the character and audience come together. The audience’s expectation of a happy ending, despite the current circumstances, mirrors Harold’s hope.

Harold Lloyd used character design and traits, cinematography, narrative elements, and ultimately the philosophies of the American public itself to relate to the audience. He is a fascinating figure in American comedy, because his comedy was so reflective of the dominant American culture in the 1920s, both in appearance and general attitude. Chaplin’s fanciful cinematic worlds, while often shimmering and beautiful, were hardly a reflection of the world as it was. And Keaton was far too fascinated with the illusions that film could create to spend his time approximating the world around him. Of the three, only Lloyd capitalized on the audience’s ability to identify with the story, images, and characters on-screen. He knew his gags and thrills were already effective, but he wanted the audience to actually care about the character in the middle of the action. Not because the character was merely the protagonist, but because the audience felt like they knew him and could understand what his hopes and dreams were. He was the boy next door; a decent, hard-working young man who just wanted to make it in this life. How much more thrilling it would be if this well-meaning, but unremarkable, young man were to scale a building, rather than some strange outsider with extraordinary skills? He may have found himself in some outlandish situations, but his reactions are believable. Fear, anxiety, disbelief, exhilaration; these are typical reactions to extreme circumstances. The unflappable Keaton or the curious Chaplin reacted to these situations in ways that were unusual or extraordinary. Harold, however, would scream, panic, and cry, just as anybody would. And it is his believable response to these outrageous plot developments that sells the reality of his films. And, as a result, his reactions make the audience relate to him on an even deeper level; his response is their response. While often described as “The Third Genius” of silent comedy – behind Chaplin and Keaton, who are regularly described as pioneers of film itself – Lloyd brought unique qualities to American comedy, helping to shape it into something more mundane, recognizable, and relatable.

Sources:

1. Kerr,Walter.TheSilentClowns.NewYork:Knopf,1975.Print.

2. Park,Ed.High-FlyingHarold.Criterion.N.p.,17June2013.Web.30Nov.2015

3. Winer,Stephen.SpeedySavestheDay!AHaroldLambAdventure!Criterion.N.p., 25 Mar. 2014. Web. 30 Nov. 2015

4. Ebert, Roger. “Safety Last.” Rev. of Safety Last. Chicago Sun Times [Chicago] 3 July 2005: n. pag. Print.