Long, Strange Trip by Scott Nye

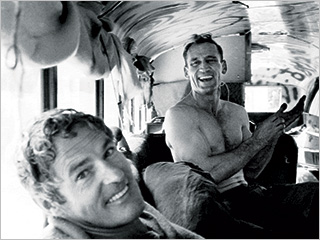

Like a great many documentaries, the degree to which you enjoy Magic Trip will depend a great deal upon your level of interest in its subject, the cross-country road trip Ken Kesey took on an abandoned school bus with a group of social outlaws in 1964. During the ride, they brought along a camera, and while their intention was to make an epic masterpiece that defined whatever experience it was they were having (as one of the subjects note, they were too old to be hippies, but not old enough to be beatniks), they were thwarted by their total lack of technical proficiency. They shot a lot of fascinating film, but often at a different speed than the sound they were recording to match it, rendering it nearly unusable. So Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood’s approach – to make a documentary about the trip and its aftermath using the footage – is practically a no-brainer, and is more than welcome to those of us who have long desired to see it.

If you don’t share my (totally sociopolitical; I’ve never done drugs and have no intention) fascination with that time in American history, I doubt there’s much here that will make you a believer. Kesey and his Merry Band of Pranksters (as they called themselves) pretty much fit the stereotype – free love, LSD, living without rules or structure – and their story is really only unique in its context. The hippie culture hadn’t really found a national foothold by this time (police stopped their bus, which was painted an array of colors, purely because they didn’t know what to make of it – the hippies weren’t on the nightly news yet). John F. Kennedy had been assassinated only a few months prior. Vietnam was gearing up, but it wasn’t the national nightmare it would soon become. What Magic Trip is, more than anything, is a journey into that moment just as the tree starts to fall, when you can sense a change in the air that it will all soon come crashing down.

The film sticks to the narrative that everything changed after Kennedy died, but the Pranksters journey feels more fueled by the optimism typically associated with the early 1960s than anything else. It’s as though Kennedy’s assassination exploded the conventions of American life, and their road trip was an attempt to discover what that term could come to mean. Their journey isn’t presented as an attack on the mainstream, but rather a group of people who just never quite fit in who are exploring their options. This initial hope makes it all the more crushing when (spoilers for history) Kesey is eventually imprisoned for drug use and made to publicly renounce the culture he had really only begun to built. This is only in 1965, a year after the trip, but between those two points you can already see the narrative for the next twenty years – the way the counterculture, the true counterculture, would be efficiently regulated, marginalized, and soon outlawed.

The footage is indeed pretty remarkable, showing the ins and outs of life on the road, leading to New York and back again. Gibney and Ellwood (co-directors on the film) have a treasure trove of material to work with, including the audio tapes from Kesey’s initial, government-funded experiments with LSD, and as a structural unit, the film sometimes suffers for it. There was no graceful way to dive into the time when the government hired Kesey to test the effects of LSD, but it’s such amazing material that there’s no way you can’t include it. On the other hand, I don’t think a section diving into Kesey’s dislike of the film adaptation of his One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Next was really necessary (but, as with most everything else here, is delightful if you agree with the points being made).

The film follows a sort of rise-and-fall narrative, but for the most part is happy to just take the ride, which is probably the best approach here. I’ve only seen one of Gibney’s films – Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer – previously (this is Elwood’s feature debut, having edited many of Gibney’s films), and this shares a common thread with that film in that it’s pretty unapologetic about taking a definite side. So there are many reasons to not see this film if none of this holds any interest to you, but many more if it does. It runs a scant 107 minutes, but packs a lot into it – the footage the Pranksters shot runs nearly constantly throughout the picture (the only major pause is for the aforementioned side trips into medical experiments and literary criticism), and it’s never boring if you’re into that sort of thing. Buy the ticket, take the ride.