Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love: The Angels Forget to Pray for Us, by David Bax

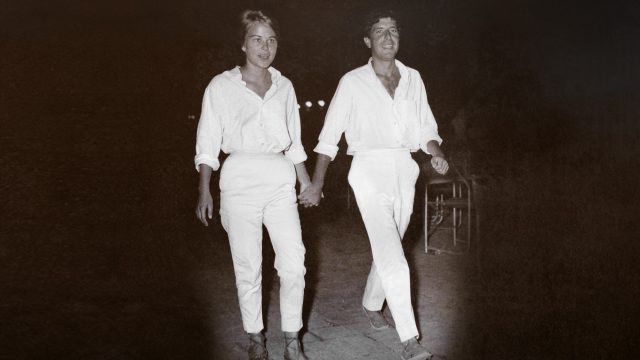

For a pretty good percentage of its runtime, Nick Broomfield’s Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love is less about the people named in its title than it is about a small Greek island named Hydra. Though all the property has apparently since been bought up by wealthy folks, the island was, in the 1960s and 1970s, a kind of de facto artist’s retreat. Leonard Cohen lived there on and off during this period and after, along with his girlfriend (and, later, lifelong friend) Marianne Ihlen. As it turns out, Broomfield himself also spent some time on Hydra and he too knew and befriended Ihlen.

That gives Marianne & Leonard a distinct charge. Instead of only being the typical bio-doc, it is also, to some extent, about how a massively successful and beloved artist affected someone the director cares about personally. Too much of the time, though, it actually is just a typical bio-doc.

Of course, that’s not to say that the life and career of Cohen isn’t worth learning about. Here is a man who stumbled trepidatiously into songwriting after some success as a poet and novelist, became a kind of coffeehouse heartthrob and womanizer, toured and performed at mental institutions after his own experiences with depression, dabbled in Scientlogy and EST (according to the film), lived in a monastery for five years in his 60s, went bankrupt and then enjoyed his biggest commercial acclaim in his 70s and 80s. It’s a fascinating story but Ihlen’s name is first in the title and a lot of this stuff has nothing to do with her.

Broomfield employs lots of revealing archival footage, including a delightfully funny moment of Cohen shaving his face backstage while tripping on acid. But frustratingly, he gives us far too little of Cohen performing. When we do get concert footage, he too often cuts away just as the song is getting going. In that sense, Marianne & Leonard fails the standard musical bio-doc test of not being more worthwhile than just listening to the artist in question.

Broomfield has a history of injecting his own diaristic elements into his documentaries. For once, though, he actually is a part of this story. Marianne & Leonard is, unusually, at its best when the director’s own feelings and accounts enter the picture. For all that it falls short as a biography, it succeeds when it approaches autobiography.

Usually, when Broomfield makes celebrity-focused documentaries, they verge into the sensationalistic (Biggie and Tupac, Kurt & Courtney, Whitney: Can I Be Me). This time, though, he actually redeems himself. In its final passages, Marianne & Leonard gives justice to a woman who has too often been reduced to Cohen’s “muse.” Broomfield ensures we see Ihlen as a person, a mother and, most movingly, a friend.