Scott’s Top Ten of 2019

As the new year and decade begins with a fresh horror show promising war, famine, and all manner of destruction, we can take really the most trifling degree of solace that the arts are reflecting our shared disillusionment and hopelessness. The United States put as its foremost concern the freedom of speech, and contrary to the pitiful cries of those who have never once been truly oppressed, speech has never been freer. So free is speech that entire new realities can be invented whole cloth with little considerable opposition.

The least we should expect is to see this same freedom trickle down into a robust, exciting, provocative, and ever-shifting cinema, and on some level, it has. My own top ten list offers ten films from at least eight countries (modern financing has never been less discernible) and ten different U.S. distributors. This speaks to a robust landscape, and makes all the more pathetic how monopolized the cinematic culture has become, both in practice – as Disney gobbles up the plurality and often outright majority of theatrical screens and box office dollars, while “is it on Netflix?” remains the arbiter of what gets seen at home – and in thought, as the self-appointed soldier of commerce guard carefully against criticism of big-budget properties. “Let people enjoy things!” they cry, as though the (let’s-pray-it’s-)late-stage capitalism they cheer hasn’t trounced from our cultural menu the very things the rest of us once enjoyed. You couldn’t have a serious interest in contemporary motion pictures without at least acknowledging the Marvel Cinematic Universe; a truly sad state of affairs, and I have thus paid my dues. The sweet relief that came from the arrival of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood this summer, a film in wide release actually worth discussing and which was greeted with largely serious discussion for and against, only served to clarify how banal the cultural discourse so often is, as a direct result of the so-often-banal entertainment offered.

That my list of the best films of the year offer “content” (the most horrid of words with which to regard art) from neither the Disney nor streaming factory is, ultimately, coincidence rather than determination, and it would be foolish to deny the multitude good the streamer has accomplished with their considerable cultural footprint. It is not ultimately their fault that the average American worker has so little in the way of disposable income (combined with studios’ ever-growing demands on theatrical exhibitors, which has skyrocketed the average ticket price over the precise period of time correlated with Americans’ diminished purchasing power) and necessarily seeks a one-stop shop for their entertainment options, and the stop’s inclusion of new films from Martin Scorsese, Noah Baumbach, and Steven Soderbergh does not go unnoticed.

So, yes, the speech is free, though not always free enough to make itself immediately and widely available, nor ultimately significant enough to change the course of history. Often it seems – even at its most thoughtful and accomplished – only to give us momentary respite from the degradation of the planet, the immense suffering we see all around us, and the fear that we are, semi-equally and certainly collectively, on some level responsible.

Honorable Mentions (The Studios Are All Right Edition) – Us, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Gemini Man, Ford v Ferrari, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood

11-15 (choose your own adventure order) – Uncut Gems, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Diane, Synonyms, Honeyland

10. The Image Book (dir. Jean-Luc Godard)

“Man’s true condition…to think with hands,” Godard reflects near the start of his new film, which feels like it’s operating at the speed of thought, made reflexively and intuitively. A bit of insight from Swiss writer Denis de Rougemont, it isn’t, so early in the film, the first quote Godard employs, in a film so dense with quotations and references that the vast majority will sail over most viewers’ heads. Most especially, a late narrative involving a Middle Eastern country might not even register as the fiction it is, let alone as an adaptation of a French novel, let alone as a larger reflection of the west’s indifference to that regions political and cultural history. Godard justifies all this late in the game through yet another quotation, this one identified (from Brecht) – “Only a fragment carries a mark of authenticity” – before letting in his most vulnerable touch, a bit of garbled narration that gives way to a coughing fit before he can complete it. He freely employs images from the earliest of silent films right up through Michael Bay’s 13 Hours, and much of his own work in between, all of which has been mashed and over-saturated and burned to the point of near-unrecognition. Far from bastardizing them, this process instead makes them Godard’s own, making the film at its most base level a beguiling, transfixing aesthetic experience for the eyes and (especially in a surround-sound setting) the ears.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD, Kanopy, and VOD platforms

9. Aniara (dir. Pella Kagerman and Hugo Lilja)

A space cruise makes a routine trip from Earth to Mars, offering its passengers all the luxuries they’d need, from spas to shopping malls to a sort of cinema that replays the happiest memories of Earth. A collision happens, their fuel storage is destroyed, and their trajectory thrown off. They are now drifting, hopelessly. The years pile up, and the desire to live, let alone to provide a future for the children they keep having, becomes vastly outweighed by the desire to forget their own doom. In a year of bleak, depressing space movies (shout out of the also-excellent Ad Astra and High Life), no film so thoroughly depressed me as Aniara, not because it reconfigured my outlook, but because it reminded me, as the destruction we face at the hands of climate change grows ever near, of the fate we all face, and how pathetic we are in constantly trying to avoid it.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD, Hulu, and VOD platforms

8. Non-Fiction (dir. Olivier Assayas)

While too many of our great contemporary auteurs are content to run from the present with an array of period pieces that, however challenging, still offer the comfort of a bygone era we can fully comprehend, Olivier Assayas has been steadily, for decades now, been exploring that very impulse through stories of people who wrestle with their place in an ever-changing society. Non-Fiction is in some way his lightest treatment of this subject, situating us among the adulterous predilections of writers, publishers, political activists, and actors, but its bemused exterior is precisely that of the moneyed creative class, whose abundance of downtime allows their disagreements about the cultural value of electronic media (the film’s original title was e-Book) to take on the importance of foundational beliefs upon which relationships are formed. But are those relationships formed by shared beliefs, or are beliefs encouraged by their relationships? It’s a thinking film that doesn’t instruct, only explores. Shot on 16mm and destined for digital platforms (from cinema to Hulu, its current home), it is itself a sort of object out of time.

Available on Hulu and VOD platforms

7. Parasite (dir. Bong Joon-ho)

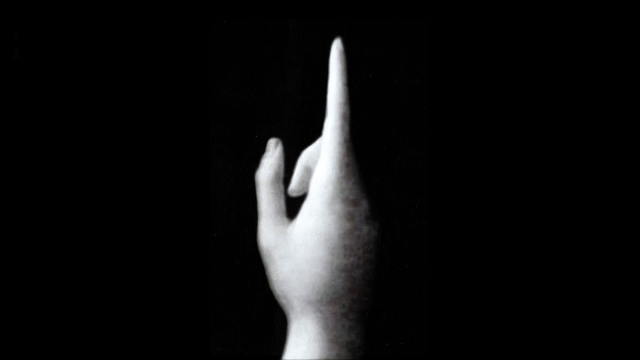

There isn’t a frame out of place on this thing, and far from feeling like an insulated object, Bong Joon-ho’s Palme d’Or-winning masterpiece is instead alive at every turn, reacting to its thrilling narrative as much as telling it. Look at how even the briefest of frames, like the iconic one above that lasts for all of a few seconds onscreen, directs our attention, how the performances command it, and how Bong’s camera warps that most grounded reality (the rich are ever-powerful, the poor fight for the scraps) into something inexplicably electric.

Currently in theaters

6. La Flor (dir. Mariano Llinás)

Anything less than the highest exaltations for Mariano Llinás’s decade-in-the-making, shape-shifting, channel-changing, ever-expanding narrative wonder will ultimately feel insufficient. So ostentatiously ambitious is his 14-hour wonder of a creation that the theatrical venues it necessitates scarcely had the capacity for it, leaving it destined for many a home screen, where its audiovisual accomplishment will naturally feel less overwhelming, where too the growing camaraderie one shares with the deranged few who dedicate a weekend to its consumption will be all but removed. All we are left with, then, is a monument not only to storytelling, but to the collaborations one forges in telling it. Llinás set out on this project after being immediately drawn to a small theatrical troupe of four women, and the way the film – through six semi-discrete episodes – comes to explore that impulse and the toll it takes over ten years – is astonishing in its honesty and eventual contentment. Undoubtedly the cinematic experience of the year, I could not wait to see what was in store for us after every break.

Temporarily unavailable; coming soon to VOD platforms

5. Hotel by the River (dir. Hong Sang-soo)

Hong has worked relentlessly, almost compulsively, over the past ten years, turning out fourteen features and two shorts from 2010 through 2018, finding only occasional U.S. distribution until his sudden breakthrough with 2015’s Right Now, Wrong Then (all but one of his six features since then have hit commercial screens stateside). That he is now a regular fixture for my lists is a true pleasure, particularly as his films have become less schematic and more intuitive as he’s pressed on. Hotel by the River, the rare Hong film to employ a handheld camera, is undoubtedly the loosest of the decade, filling the narrative space with naps and wandering amidst a semi-purgatorial hotel that seems to swallow its inhabitants up into other dimensions and spit them out the other side. It’s a sad, mournful film, in part because Hong seems to finally begin to accept rather than rebel against his advancing age (he’ll turn 60 later this year), but one that’s unexpectedly sweet, including scenes exchanging gifts and unexpected snippets of his poet (played magnificently by Ki Joo-Bong) playing with animals and chopping wood. The striking black-and-white cinematography casts the snow-filled landscape as impenetrable, those rare moments of sentiment cut with icy, chiseled monochromatic frost.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD, and VOD platforms

4. Frankie (dir. Ira Sachs)

The too-brief theatrical run of Ira Sachs’ exquisitely-composed meditation on family and mortality did not allow me a second viewing to dissect how exactly this seemingly-slight wonder left me as close to tears as I can get by its conclusion, so I can only trust the immediate, overwhelming emotional response I had to it initially. Isabelle Huppert plays Frankie, a French actress much like Huppert herself. (Hopefully) unlike Huppert, Frankie is dying, and has gathered her unknowing family and friends to Sintra, Portugal for a scenic goodbye. Somewhere between Rui Poças’ impressionist-tinged cinematography, the languid pacing of the dialogue, the glances of regret and abandoned feeling in the note-perfect cast (especially Marisa Tomei, giving one of the best performances of the year), and the space Sachs gives them to relish in the environment and one another lies the fount of feeling one searches for in all art. I mourn for a cinematic culture that identifies more directorial force and power in something like 1917 than this, which is perfectly-tuned a piece as I’ve seen all year.

Currently unavailable, coming to Blu-ray, DVD, and VOD platforms in February

3. Transit (dir. Christian Petzold)

A complex path of sudden work, purpose, and misunderstandings leaves a German rebel living under the identity of a writer in the port city of Marseille, a purgatorial passage of escape from Europe for many refugees in World War II. Taking the plot of a 1944 novel by Anna Seghers and setting it, somewhat, in our contemporary world leaves the title with at least two of its innumerable meanings, and we’ve barely gotten off and running. Petzold has continually revisited the idea of a stasis before escape, should such an escape even prove possible, and his interest in this theme has found an bittersweet alignment as the liberal world has taken a renewed focus on the plight of refugees. Once the subject of many an Oscar tear-jerker, are no longer escaping a Nazi regime we have semi-successfully cast in history as evil, and can feel better than. The contemporary political forces casting them out, we’re told, are more “complicated” than Nazism, even as the suffering they wreak is too often comparable, and we have no longer the comfort of history to look back on and say “we shall do differently.” By casting those old narratives in contemporary turns, Transit reminds us both of the real evil we face today, and of the danger in our own complicity, wrapped up in a ghost story for the living that is as haunting and thrilling as the best film noir.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD, and VOD platforms

2. The Souvenir (dir. Joanna Hogg)

“Why doesn’t she just leave him?” I would like to no longer endure this question about The Souvenir or any other piece of art, but from the auditorium where I viewed it right up ’til today on social media, I’m afraid I will continue to do so, and I will continue to reply as I have – I deeply envy those who can comfortably ask that question. Hogg’s fourth film, quite autobiographical from what I’ve read, does indeed tell the uncomfortable story of a young woman who gets involved with a man who treats her quite poorly, and who forgives him all manner of unforgivable acts in order to retain the relationship, some fragment of the initial sweetness she found in him. It is an uncomfortable truth to acknowledge that many of us would, at some point in our lives, gladly endure cruelty to hold onto some semblance of love, to forgive anything if it meant one more sweet word. Hogg digs into the naiveté about the larger world that drives such desires, and her cast – lead by the extraordinary Honor Swinton-Byrne and Tom Burke (best male performance of the year, hands down) – relishes the immediacy of their young desires. Set in the past, and filled with the details of a passing period and fading youth, The Souvenir is almost-contradictorily rigid in its composition, a steady succession of note-perfect images that might seem too insulated did they note culminate in a (for me, literally) breathtaking conclusion that assaults whatever complacency we might have remaining.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD, Amazon Prime, and VOD platforms

1. A Hidden Life (dir. Terrence Malick)

If, on some level, you’re not considering the role of the average citizen under a fascist regime, I encourage you to begin doing so, and Terrence Malick’s latest masterpiece proves fertile ground on which to nurture this exercise. It takes absolutely seriously the true story of an Austrian farmer who refused to join the German army in World War II, having identified that which his countryman so seek to ignore – that he’d be serving an evil cause. Malick explores the duality of this decision with uncommon grace, recognizing the hypocrisy of audiences who seek out these narratives yet are unprepared to take such a stance themselves, and everything Franz will sacrifice by dedicating himself to it. Malick understands that Franz’s family will undoubtedly be worse for his decision, but that society might benefit one day from his example, from knowing it is at least possible to refuse service, and the freedom that comes with what is otherwise unending confinement and punishment. As he did with The New World, Malick uses the letters his characters wrote at the time to inform his characteristic voiceover, finding in it voices in harmony with his own, and a true love that can help endure even the most senseless of crimes – destroying a person for refusing to aid violence.

Currently in theaters

My understanding is that disposable income is about as high as it’s ever been in the U.S, and people have more options for viewing than ever.

Good thing he specified “worker” and not “investment vampire” but yeah, per capita math is tough.