Sundance 2021: Wild Indian, by David Bax

Nearly everything about writer/director Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.’s Wild Indian appears intended to be taken more metaphorically than literally. The characters and events are symbols (well drawn and well acted ones). The fact that the Native American children in the movie’s 1980s-set first half attend a Christian school represents the tools white people have used to erase Native culture and identity; the fact that it’s specifically a Catholic school feels like a hint of the themes of guilt and vengeance Corbine has in store for us. But the allegorical nature of Wild Indian‘s ingredients is by no means a shortcoming. A story with ideas as big as these on its mind sometimes requires metaphors to make sense of them.

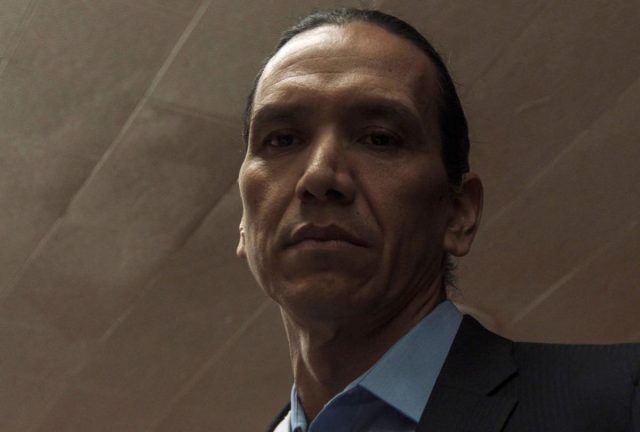

Makwa (Phoenix Wilson) is a kid who’s having a tough time of things. He’s unpopular at school and, worse, chronically abused at home. His only friend is Teddo (Julian Gopal), who often steals the rifle from his father’s closet so the two boys can sneak off to the woods and shoot at bottles. One one such excursion, Makwa takes aim at something else, leaving the two boys with a terrible secret. In Wild Indian‘s second half, we jump ahead 35 years. Makwa (Michael Greyeyes) and Teddo (Chaske Spencer, from Alex and Andrew Smith’s Winter in the Blood) have grown apart until a decision made by Teddo forces them to face one another and what they’ve done.

Wild Indian‘s two halves address two different, well-known axioms that are no less true for how often they are invoked. First, “hurt people hurt people.” Makwa has been dehumanized by those with power over him (again, a metaphor for the treatment of this land’s native population by the country that occupies it) and revisits that inhumanity on those around him. Second, “silence is violence.” The lifelong refusal of the two men to address what they’ve done and seen means they revisit the pain they’ve caused upon their victims every single day.

Corbine’s metaphors don’t only exist on the page. His mise en scène contains visual touches both subtle (the artwork on the walls of adult Makwa’s luxurious apartment pay cynical lip service to a heritage he otherwise ignores) and powerfully immediate (a bullet’s shell looks much smaller in a man’s hand than a child’s, an observation with horrifying implications).

Wild Indian has much in common with another recent film, Ramin Bahrani’s The White Tiger. Though Corbine’s take on the subject matter is more meditative and minimalistic, both are stark and sober comments on what is required of someone who wants to “succeed” in a cruel world with sick values.