TCM Fest 2013, Part Three: The Marriage Circle, by Scott Nye

If one sees a decent number of classic films, themes of marriage will inevitably recur. Sometimes used classically for commitment and undying love, other times to indicate sexual passion, and just as often to comment on the rigors of contemporary life, matrimony is never far from the minds of many films made from the 1930s-50s. Trap, challenge, fling, or fiasco, a whopping seven films at 2013’s Turner Classic Movies Classic Film Festival gave you a pretty good look at the joy of getting hitched.

There are about a half-dozen marriages in Jack Conway’s absolutely wonderful 1936 screwball comedy, Libeled Lady, starting with one between Spencer Tracy and Jean Harlow, the former of whom ends up slipping out the back door to manage a crisis for his newspaper, and her storming into the office of said scandal sheet, fully adorned in her wedding dress. It’s but the start of a series of great star entrances (Myrna Loy will soon emerge from a sweatshirt, as if bursting into view, and William Powell will be introduced via a large bill he owes a too-lavish hotel), leading up to the scheme of the century. See, the newspaper crisis happened because Tracy’s rag accused socialite Loy of aiming to break up a marriage, only she’s as well-mannered as they come, so to avoid a costly lawsuit, Tracy enlists the services of that most charming of journalists, Powell, to pose as a married man for Loy to seduce, thus retroactively proving the paper’s claim. The only hitch, so to speak, is that to make the marriage stick, they have to find a woman to act as Powell’s wife, and while Tracy may have a woman willing to do anything for him in Harlow, she’s getting mighty tired of these games he plays, and he hasn’t even begun to consider what would happen if she and her make-believe beau should happen to actually get cozy.

It’s about as great a premise as they come, especially as the complications, assumed identities, miscommunications, and outright lies pile on top of each other, culminating in a sort of “well, away we go!” climax. Each character is so sharply and distinctly established that there are few surprises, but endless delights, and the subtle shifts each relationship undertakes are inevitably as much the result of genuine change as self-delusion. When Harlow and Powell are first “introduced,” she is so outrageously disgusted by him that we wonder if they hadn’t met before, under circumstances best not discussed around Tracy, making her eventual attraction to the former all the deadlier. But marriage is, ultimately, a game to this bunch, and the film really uses it mostly as an analogy for sex – intentions towards marriage turn the way someone might try on a string of lovers, or string on a lover, or string together a plot for love. Or money. I’m always going on about how, despite not producing the bulk of my favorite films, I’d sooner watch a film from the 1930s than any other decade, and the sort of boundless disregard for morals or good intentions in the name of entertainment proves a joy at every turn in Libeled Lady.

Sex is much more the subject-on-the-edges of Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s classic 1949 musical On the Town. “What?” you ask. “A movie my grandmother watches that’s secretly all about sex?” And how, my friends, and how. On the Town opens with three sailors – Gabey (Kelly), Chip (Frank Sinatra), and Ozzie (Jules Munshin) – bounding off a boat for a night of leave in New York City. They’re hoping to see the sights, certainly, but also, hopefully, get lucky. And not in any kind of finding-my-soulmate way, either (the hoots and hollers that greet the initial “what do you think could happen to you in one day?” question say it all). Okay, perhaps Gabey’s intentions are a little bit more classically honorable, and Chip genuinely does want to see Manhattan’s many landmarks, but get him cornered in a bedroom and he’ll hardly be scrambling for the exit. Ozzie, meanwhile, is just overjoyed that a woman finds him to be an excellent anthropological specimen, especially when she reveals that she took up the subject as a way to stop hooking up with so many men, though it’s not exactly working – if anything, she’s just found a way to academically rationalize her more base urges.

The film makes no such effort. Rather than moralize, let alone demonize, the actions of sailors on leave (and not even during wartime, at that), it celebrates the sort of sudden connections one can strike up when the clock’s a-ticking, and by the end of the night, the wistfulness in the air is not too dissimilar from more actively-championed romantic fair like Before Sunrise, only without the delusion of future reconnection. Should they meet up again, all the better, but all that matters in the meantime is that they shared this meal, this dance, this stroll, this song atop the Empire State Building, and this roll around the couch after successfully kicking out the roommate. It being a Kelly and Donen affair, and an early one at that (despite ghost-directing several pictures, this is the first on which they each received a directorial credit), it’s almost exploding with the joy of song and dance, and it certainly helps that they had some great numbers to celebrate, from the pure explosion of the opening “New York, New York” to the sly romance of “You’re Awful” to the outright lustful “Come Up to My Place” (sung by a woman, no less). I’d woefully underestimated the picture when I first saw it some years back, but even a glimpse at the brand-spanking-new 35mm print they showed at the Egyptian Theatre for the festival (and man, did it look spectacular) was enough to send it skyrocketing. It closed out my Friday, and was the perfect way to end a day.

Brand-new 35mm prints and musical numbers come together again in what became the talk of the weekend, the where-the-hell-did-this-come-from 1933 discovery I Am Suzanne! Now here’s the thing – you’ve seen many aspects of this film before. You’ve seen the film where the gorgeous, successful woman falls for a man of much lower stature whose passion makes up for everything he lacks that her more moneyed-and-studied suitor possesses. You’ve seen films in which men try to put women in a box, only for her to emerge triumphant. You’ve seen backstage dramas aplenty. I can virtually guarantee you’ve never seen anything like I Am Suzanne!, which places these elements in the weird, wild world of puppet theatre, into which a titular dancer (Lilian Harvey) ends up after a particularly nasty spill during a particularly dangerous routine. She’s cared for primarily by Tony, who not only looks out for her personally and professionally, by teaching her the ropes (haha) of the puppet business, but brings her out from under the domineering wing of her manager, best known about town as the Baron, and even starts to fall in love with her a little.

Unfortunately, even nice guys can have a streak of the perverse within them, and it’s not long before Suzanne realizes that Tony’s affections for her are slowly warping into a desire to make her just another puppet (though, given the uncomfortable amount of affection he affords them, isn’t quite as bad as all that, except for that uncomfortable-amount-of-affection-for-puppets thing). Marrying for romance is a relatively modern conceit, and this film represents something of a last straw for the days of marriage being mostly a possessive pursuit, as Suzanne feels at first comfortable in the overly-protective arms of the Baron, and then Tony, only to find their grasp far too tight. Her eventual realization of the soon-to-be-literalized Hell into which she has let herself be trapped is easily the film’s standout moment, as puppets begin to mingle with people in a spectacularly nightmarish fashion. The puppetry was conducted by the Yale Puppeteers, a professional outfit that ran a traveling show before opening their own permanent theater in Hollywood in the early 1940s, running steady through most of the 1950s, and, especially early on, regularly selling out to many of the entertainment industry’s biggest names.

That “brand-new 35mm print” bit was especially true here, as archivist Katie Trainor explained in her introduction, noting that we were the first audience – public or private – to see their restoration work, and that it was just barely printed in time to make this screening. Just the fact of its presentation is a perfect display for what I most love about TCM Fest, introducing these absolutely bizarre features that might not have any overt commercial value, but which is able to gather an eager crowd (enough for them to play it again in an encore screening) through the prestige of the festival. Needless to say, it looked great.

Marriage-as-possession takes on much a more embedded, widespread role in Vincente Minnelli’s 1955 Technicolor CinemaScope musical spectacular, Kismet, a film which, according to star Ann Blyth (who appeared in person for a short Q&A session before the film), Minnelli wasn’t terribly interested in making, and unfortunately that’s pretty obvious. According to Blyth, Minnelli only made the picture to get his upcoming Vincent van Gogh biopic Lust for Life greenlit, and his mind was mostly on that during the production of this. Howard Keel, in the lead role as the father who swindles and bargains his way up the ladder of Bagdad society, but neglects the needs of his daughter (Blyth) along the way, really goes all out, and the film certainly comes alive when he’s onscreen, but it only brings into sharp focus just how leaden most of the rest of the picture is. Naturally, when the camera can sit back and observe a dance scene, there’s some life there, but there is perhaps no easier task than making dance look at least pretty good on film

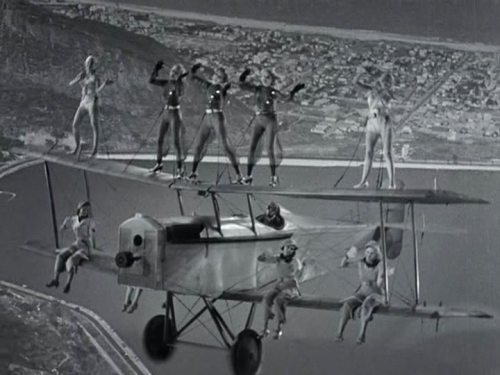

Musicals almost aren’t even musicals without a touch of romance, though, so it’s little surprise we’d find ourselves revisiting this theme with Flying Down to Rio, a sort of wannabe-Busby-Berkeley picture (it went into production in August of 1933, six months after Berkeley’s career-defining 42nd Street came out), but, hey, even in the shadows of such endeavors, there’s still space to shine. More relevantly, perhaps, this was the debut of the Astaire & Rogers dance team, which would go on to dance their way through nine more pictures by the time they were through, but were just as close to never being. Reportedly, Rogers wasn’t particularly keen on the assignment, her first for RKO, who had just signed her to a seven-year contract, as she was looking to turn away from musical comedies towards more dramatic roles. Nevertheless, she told Astaire might be fun, and either she’s a particularly good liar or managed to convince herself, because it’s very easy to see why the audience’s eyes were filled with hearts and the studio’s with dollar signs. Despite being the story a bandleader’s attempts to court a South American heiress who’s pledged to be married to another, the film deflates whenever they’re onscreen, only to be reinvigorated to the point of bursting whenever it turns back to the dancers.

By the time they do, indeed, fly down to Rio de Janeiro, the ostensible leads are practically background players amidst the increasingly-ostentatious musical numbers, culminating in the kind of scene that even Berkeley (in my experience) wasn’t audacious enough to pull off, though admittedly this is far less graceful. Still, the spectacle of dozens of showgirls dancing on top of and across a dozen biplanes is quite something; even though it’s all very obviously simulated, it’s a hell of a show.

Cybill Shepherd, of all people (not that I’m complaining, mind), showed up beforehand to discuss the picture, largely from a fashion perspective. She also noted that the Carioca dance (excerpted below) was the most immediate craze following the film’s release, and it’s easy to image its success was, for a time, intertwined with the public’s fascination with Astaire & Rogers, and vice-versa. More amusing for us cinephiles, Shepherd related how Peter Bogdanovich, when they were first dating, would drag her to dozens of films, always preferring the Lubitsch musicals and the like, but she would insist, from time to time, on an Astaire & Rogers joint. Good stuff.

So we come to the genuine romance, the ideal instigator of marriage, and one at which the screen excels at relating, given the limited timetable on which it operates, the pure emotion of a good close-up, and the room for reflexive chemistry in a great two-shot. What better way to get into this than with Frank Capra’s absolute classic, easily my favorite film of his, and one of the greatest romantic comedies ever made, It Happened One Night. Despite this being practically the definition of “my taste,” I had only seen this picture once previously, but I was surprised and largely delighted to find it’d hardly slipped from my memory. Some just stay with you. On the off-chance I need to recount its plot, the film follows ousted newspaperman Peter Warne (Clark Gable) as he attempts to reclaim his reputation, and job, by means of reclaiming the spoiled-rotten escaped heiress Ellen Andrews (Claudette Colbert), who’s run away from home after marrying, much against her father’s wishes, reputed male gold-digger “King” Westley. Life on the road proves too demanding for a girl who’s never considered money, let alone the little she’s left with after a series of poor decisions, but Peter strikes a deal with her – he’ll help her reunite with Westley in exchange for an exclusive on her story. Of course, if she’d rather, he could always just call her father and get some of that sweet reward dough…

And so they’re off, by bus, by foot, and by car, and anyone who is even aware of the hundreds of romantic comedies that imitate this can guess where it’s headed, but how. Despite what has been widely reported to be a pretty rough shoot (neither Colbert nor Gable really wanted to be there, having been loaned to Columbia from their respective studios, and clashed with Capra throughout production) the one element that went absolutely right was the only one that needed to – the two stars got along marvelously, and it shows. Good chemistry can, and has, been faked, but Gable and Colbert have something else, a natural ease with one another that, even when they’re bickering, keeps things nice and playful. When they start to get tender, it becomes almost heartbreaking, but Capra’s real genius stroke here, and retrospectively most ambitious, is never showing us the two leads after they finally fall in love. The very last scene we see of them together, they’re still at each other’s throats, and when we rejoin them on the eve of marriage, they’re nothing more than, as Herman’s Hermits famously sang, two silhouettes on the shade, if that. Simple, sweet, and, with the blow of a horn, triumphant.

And finally, what would a series of films dealing with marriage be if at least one didn’t acknowledge divorce, or rather, as they used to call it, the comedy of remarriage. Mitchell Leisen’s absolutely stunning 1947 entry into the genre, Suddenly, It’s Spring, wasn’t just one of the best films I saw during the whole of TCM Fest, but will almost certainly go down as one of my favorite discoveries of the year. It’s weird that we’ve gotten to a point at which Fred MacMurray’s reputation has completely reversed from what it was when he was actually a star. Back then, he was known for being a sort of foppish sort, but now we know him primarily for his darker roles in Double Indemnity and The Apartment, and these seem like the odd ones. Too bad, too, because he’s really tremendous here, as a man welcoming his wife (Paulette Goddard) back from the armed services, where she was a counselor (they’re both lawyers, in fact) for other enlisted women whose marriages were on the rocks, only to greet her with a divorce. Apparently they’d talked things over before going off to war, but her experience with other troubled couples has given her something of a new desire to make things work. He, however, is more interested in the woman with whom he’s taken up, who’s pretty insistent about this whole divorce thing.

As good as he is, though, this is really Goddard’s show, and she owns absolutely every scene she’s in, not only from a character perspective, but an acting one as well. The scenes between her and her husband’s new sweetheart are laced with the sort of underhanded, biting remarks that women so expertly use to insult one another while maintaining polite company (MacMurray remains oblivious to it all), and of course, since we’re rooting for her anyway, Goddard always comes away with the best line. Meanwhile, MacMurray’s best client can’t help but charm Goddard at every turn (or at least try to), introducing that wonderful tension that comes when a man chases after a woman in whom you claim to have no interest, until, well, he came along. But the sense of longing, even before MacMurray admits it, between he and Goddard, laced with the wild screwball and slapstick comedy, is absolutely winning. It’s damn near criminal that this isn’t available on DVD, or even VHS for that matter (though the enterprising cinephile can find avenues), but perhaps that will change one day. Until then, do keep an eye out for this one; it is exceptional.