The Tragic Comic, by Darrell Tuffs

The Gold Rush (1925) is a silent comedy film; it was directed by Charlie Chaplin and produced under the newly formed production company, United Artists. Prior to making The Gold Rush, Chaplin had only directed two feature films, the first was The Kid (1921), of which, was primarily a comedy, and featured Chaplin’s globally famous screen icon “The Little Tramp”. The second, A Woman of Paris (1923), was a somewhat dark and tragic drama, to which, Chaplin states in text before the film opens “… to avoid any misunderstandings … this is my first serious drama”. A Woman of Paris was a box-office failure, but within it (and his earlier short films), Chaplin, a man best known for encapsulating a comical and entertaining clown figure, expressed a deep interest in drama and the tragic. In 1925, while making The Gold Rush, Chaplin would return to comedy and his classic “Little Tramp” character, only this time, introducing undercurrent tones of deep depression and desperation more tragic than anything he had made prior, while at the same time, making audiences laugh just as hard. How and why did Chaplin make one of cinema’s classic foundational comedy films under such darkly tragic themes?

In his autobiography, My Autobiography (1966) Chaplin explains that one morning he sat, “looking at stereoscopic views … with a long line of prospectors climbing up over (a) frozen mountain. … Immediately, ideas and comedy business began to develop. In the creation of comedy, tragedy stimulates the spirit of ridicule; because ridicule, I suppose, is an attitude of defiance: we must laugh in the face of our helplessness against the forces of nature – or go insane”. Chaplin then goes on to state his interests in, “the Donner party who missed the route and were snowbound in the mountains of the Sierra Nevada. Out of 160 pioneers, only 18 survived. Some resorted to cannibalism, others roasted their moccasins” (Chaplin, 1966, p.299-300). From these unlikely influences, Chaplin creates the darkly comic plot of The Gold Rush, rooted in death, hunger, and cannibalism. Within these ideas, Chaplin’s earlier attempts to create a serious drama had combined with a more commercially successful comedic tendency; to create what Chaplin subtitled “A Dramatic Comedy”. Regarding this, Gene D. Phillips states that, “Chaplin brought with him to (The Gold Rush) the experience gained in directing a drama … The Gold Rush has scenes that are almost straight drama … the humor in The Gold Rush rises directly from the serious situations in its story” (Phillips, 1999, p.27). Phillips hits upon a key note in addressing the reasons why, at this time, Chaplin’s films were daring to branch into darker territory. As Chaplin grew as an artist, the side of him that deeply wished to be taken seriously as a director of drama began to integrate with the successful clown the world had first fallen in love with. It would appear that Chaplin’s themes grew more tragic during The Gold Rush in order to satisfy both of these contrasting personas within himself. The Gold Rush may be seen to wholly represent what Wes D. Gehring calls, “Chaplin’s most frequent and creative depictions of dark comedy” (Gehring, 2014, p.80).

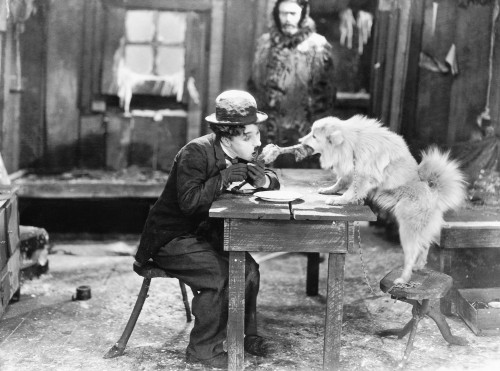

Returning again to his autobiography, Chaplin also states, “Out of this narrowing tragedy I conceived one of our funniest scenes. In dire hunger, I boil my shoe and eat it, picking the nails as though they were bones of a delicious capon, and eating the shoelaces as though they were spaghetti” (Chaplin, 1966, p.300). The scene is deeply comical, perhaps one of cinema’s greatest comedic moments, but was based upon human starvation and suffering, blending the tendencies associated with both tragedy and comedy, then highlighting the close relationship between them. As Chaplin explains in a quote from Gehring’s book, “the comedy in tragedy has always been second nature to me. Cruelty, for example, is an integral part of comedy. We laugh at it in order to not weep” (Gehring, 2015, p.23). Chaplin introduces these laughs into the shoe scene by allowing his character to act against the normality of the situation, in which audiences might expect a man starving to death to become depressed at the prospect of eating his own boiled shoe. However, as Kenneth Schuyler Lynn points out, “Charlie has prepared and served (the shoe) with cordon-bleu care on carefully wiped plates … all of Charlie’s gestures, from finger wiggles to shoulder hunchings, bespeak his appreciation of the succulence of his cooking” (Lynn, 1997, p.278-279). Chaplin breaks down any possible progression of tragic narrative within the scene, instead, using tragedy as the base on which to build a straight narrative of normality, when these elements combine, the resulting reaction from audiences is laughter and comedy. On this, Kyp Harness highlights the scene’s ability to lightly tread the thin line between comedy and tragedy, calling it “an act of ultimate desperation, an evocation of the pain of gut-grinding hunger and deprivation, the sharp, painful edges of need exposed bare” (Harness, 2008, p.119).

The Gold Rush moves even further towards tragic territory with a scene that Chaplin lightly outlines as, “my partner is convinced I am a chicken and wants to eat me” (Chaplin, 1966, p.300). The setup sounds somewhat silly, or even childish, but as with Chaplin’s earlier shoe scene, it is rooted within a dark influence, this time, human cannibalism. Alone in a deserted cabin, The Tramp’s only companion, Big Jim McKay, begins to contemplate killing and eating The Tramp. The scene holds a strong tone of comedic flamboyance; the character’s movements are completely overacted and exaggerated, but again, the surface of which these jokes stand on is harsh, tragic and barbaric. Harness points out that, “… horror has been at the heart of Chaplin’s comedy all along … Big Jim’s clear-eyed intention (is) to cannibalize his friend – only Charlie’s dexterity and ingenuity will prevent him from being slaughtered” (Harness, 2008, p.120). Gehring points out that the visual softening and narrative viewpoint technique used within the scene may distract from its darker undertones. “Though McKay’s perspective is softened by periodically seeing his hallucinated image of Charlie as a giant chicken … it is still humor anchored in cannibalism” (Gehring, 2014, p.80). The scene is a particularly interesting example of the deeply tragic roots that most types of comedy attempt to build upon, especially when taking into account slapstick comedy, of which, Chaplin’s “Little Tramp” character is considered the most famous encapsulation of.

The foreign innocence, alienation and social awkwardness of The Tramp are key elements of The Gold Rush, and are crucial to examining the ways in which the film transforms tragedy into comedy. Throughout the film, The Tramp is a tragic character; he desperately attempts to improve life for himself and others, but ultimately fails, in increasingly embarrassing ways. Never before had Chaplin placed The Tramp in such desperate and dire situations. This increased the number of potential hazards, but also allowed for a character that audiences were already familiar with to feel more significantly relatable. Jerome Larcher explains, “The Tramp now displays a sophistication that enables him to confront all types of difficulty with dignity and to survive in a brutal world” (Larcher, 2011, p.47). This new-found “dignity” within Chaplin’s character allowed audiences to appreciate his failed efforts with greater humor, meaning that Chaplin, more than ever, could be brutal and ruthless with the way he treated his character; The Tramp himself had become developed enough to feel relatable and comical, even while, essentially, starving to death. Chaplin himself once said of The Tramp, “This poor little creature – fearful, weedy, underfed … never becomes prey to the people who torment him. He rises above his sufferings; a victim of unfortunate circumstances, he refuses to accept his defeat”. He then goes on to declare, “This tragic mask has provoked more laughter than any other figure on the screen (which) proves that laughter is very close to tears” (Chaplin, 1931, p.28). As already highlighted in the innocent ways he overly appreciates his boot dish, or the cartoon manner in which he handles his own imposing death by cannibalism, The Tramp creates comedy not by simply being placed in harsh situations, but by his pathetically heroic reactions in order to cope in these situations. In support, John Fawell points out that Chaplin “continually softened (The Tramp) and became increasingly dexterous at managing his character so that his audience was taken with his charm” (Farwell, 2014, p.120). The development of Chaplin’s character over time is a key component in pinpointing the reasons that The Gold Rush could generate elements of both comic tragedy and tragic comedy. The public already knew The Tramp and understood elements of his personality from previous films by Chaplin, so were naturally more prone to laugh along at his unfortunate misfortunes. Audiences began to hate how the world often treated The Tramp, but love his desperately innocent ways of trying to succeed within it; by way of The Tramp, Chaplin transforms tragedy into comedy.

Already detailed are reasons and suggestions leading to ‘how’ Chaplin was able to so discreetly combine tragedy with comedy in making The Gold Rush. However, also needed to understand the ways in which the film works on such deep levels of pathos are the reasons ‘why’ Chaplin was first led to construct such a film. Chaplin’s well-documented childhood held a strong blend of themes present in The Gold Rush, the most prominent of these being poverty. Chaplin writes of his childhood, “When I was 11 years old, homeless and starving in London, I had big dreams. I was a precocious youngster, full of imagination and fancies and pride” (Chaplin, 1985, p.1). Chaplin’s past held many similarities to much of his later film work, in particular, The Gold Rush, which placed his character, as a gold prospector, on the direct search of a richer, more prosperous future, from an unlikely past. Larcher writes, “The myth of The Tramp resonates poetically with that of the gold prospector … The Tramp had not become an Everyman figure. Poetry made it possible to establish a critical distance from the American dream, even though Chaplin himself had come to more or less embody that dream” (Larcher, 2011, p.47). In using tragedy to anchor his story, Chaplin was able to deploy elements of himself within the film, his childhood struggles and sense of desperation, but also, his personal triumph over the American dream by way of The Tramp overcoming harsh environments in order to discover great riches. These moments of reflection upon his personal life were also beneficial to Chaplin as an image, as Mordaunt Hall alludes to with his article in the New York Times, “by all means Chaplin’s supreme effort, as back of the ludicrous touches there is a truth, a glimpse into the disappointments of Chaplin’s early life” (Hall, 1989, p.3). Even before Chaplin had become a world-famous star, his early film and acting work hinted at his future international image as a “tragedian”, as Miriam Teichner predicts of Chaplin, as far back as 1916, “He isn’t a tragedian yet – but he still has ambitions. Not for real tragedy, but for something half-way-in-between the sort of comedy he plays now and the real deep-down, shivery-music heart-throbs kind” (Teichner, 1916, p.14). The Gold Rush is a product of these elements becoming intertwined at a crucial moment, when Chaplin was at the very height of not only his creative powers, but too, his social powers; quite simply, the timing was right in Chaplin’s career for a film as darkly light as The Gold Rush.

The sources pointing to The Gold Rush as a truly tragic comedy exist in great numbers. It is clear in researching the film that the general collective opinion from scholars highlight Chaplin’s famous character, as well as Chaplin’s life itself, as key reasons that a film based upon such disastrous atrocities could have been molded and shaped into one of the greatest silent comedies the cinema has ever witnessed. Chaplin’s own autobiographies are a more than suitable starting point to grasping a sense of his history and personal intention. The work from recent and past scholars then builds upon these starting points to deliver many detailed observations of certain moments and scenes within the film, capturing the film’s effectiveness past the points of even Chaplin’s own intentions. The Gold Rush is the film that Chaplin himself stated on a few occasions he would like to be remembered by, perhaps this was because of Chaplin’s often repressed sense of fondness for tragedy, for the film holds within it, both his darkest filmmaking moments, and his funniest.

Chaplin, C. (1985) Charlie Chaplin’s Own Story, Geduld; Indiana.

Chaplin, C. (1966) My Autobiography, Penguin Books; Middlesex.

Chaplin, C (1931) “The Tramp as seen by Charlie Chaplin” extract from ‘Pourquoi j’ai choisi comme type “le desherite du monde”?’ published in Le Petit Provencal, in Master of Cinema: Charlie Chaplin, Cahiers du cinema Sarl; Paris.

Fawell, J. (2014) The Essence of Chaplin: The Style, the Rhythm, and the Grace of a Master, McFarland & Company; North Carolina.

Gehring, W. (2014) Chaplin’s War Trilogy: An Evolving Lens in Three Dark Comedies, McFarland & Company; North Carolina.

Hall, M. (1925) “Here and There with Chaplin”, in New York Times, 11th November 1925, sec. 7.

Harness, K. (2008) The Art of Charlie Chaplin, McFarland & Company; North Carolina.

Larcher, J. (2011) Master of Cinema: Charlie Chaplin, Cahiers du cinema Sarl; Paris.

Lynn, K. (1997) “Why Don’t You Jump”, in Charlie Chaplin and his Times, Simon & Schuster; New York.

Phillips, G. (1999) Major Film Directors of the American and British Cinema, Associated University Press; London.

Teichner, M. (1916) “Charlie Chaplin; A Tragedian Would Be”, in Charlie Chaplin Interviews, ed Kevin J. Hayes, University Press of Mississippi; Mississippi.