Won’t You Be My Neighbor?: It’s You I Like, by David Bax

Sometimes it feels like just about all of mainstream movie culture is powered by nostalgia. Multiple times every weekend, studios bank on us being willing to hand over some dough in exchange for a trip down memory lane, to revisit characters and scenarios we remember from our childhoods (all of which will ultimately disappoint us). But Morgan Neville’s documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, about longtime TV host Fred Rogers, takes us back to an entertainment from our youths that was as uncynical and openhearted then as it is in our memories. This is something worth being nostalgic about.

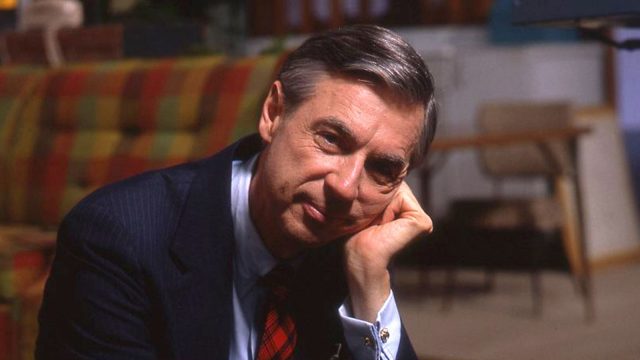

Neville’s straightforward approach simply tells the chronological life story of Rogers or, more accurately, the story of his long running television program, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. What glimpses we get of his home life or his own childhood come from the interviewees, mostly made up of his family or the cast and crew of the show (who were, it seems, a family themselves).

In keeping with Rogers’ own apparent philosophy of life, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is mostly unadorned. Of course, there’s the bit of animation requisite for any populist-minded documentary these days. Other than that, Neville’s only trick is to occasionally cut away to trolleys, like the one on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood that led to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe or the ones that carried commuters through Rogers’ native Pittsburgh until the mid-1960s. Both versions suggest being safely conveyed, a metaphor for what Rogers’ aimed to offer the children of America who watched him for decades.

Rogers was an ordained minister who saw his program as his ministry. Though the show itself was almost entirely secular, Rogers personified traits we use to refer to (but don’t seem to anymore) as Christian: Kindness, generosity, charity. The totality of his good-heartedness led some to assume he must be hiding something. Rumors ranged from his being anything from a closeted homosexual to a serial killer. In the 21st century, his innate decency exposed something sadder and more dangerous in America. This lifelong Christian conservative suddenly became a boogeyman of certain corners of the religious right that have moved into spotlight since the election of our hatred-stoking president, with Fox News and the Westboro Baptist Church denouncing him for, essentially, encouraging people to feel good about themselves, which certainly throws these hateful people’s own bankrupt philosophies into stark relief. Neville includes a clip of a Fox commentator calling Rogers an “evil, evil man,” which would be funny if it didn’t illustrate how astray some of America has gone from Rogers’ vision of universal affirmation.

But Rogers wasn’t some guileless pollyanna. It’s almost unbelievable now to be shown just how willing he was to address head on the hardest things about life–like the death of loved ones–and the negative feelings they inspire. He made no attempt to obscure the fact that sadness and anger are a natural part of life in general and childhood in particular. He told us it was okay to feel this way and, as kids, we didn’t find that bizarre because we didn’t yet know how rare his understanding was.

What does it say of our assumptions about the world that Rogers’ openness is so shocking now? And why is it so difficult for almost all of us to remember what it was like to be a kid? With Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, Neville gives us a portrait of a man who seems to be like no one else who has ever lived and then pleas with us to not let that be the case.