Castles in the Sky: Only Yesterday, by Aaron Pinkston

In 1991, Tokyo was already a massive modern metropolis. With the tech revolution in full swing and the early start of the internet boom, Japan was developing into a world leader in the industry. It is this world that Studio Ghibli’s Only Yesterday is working against. The film, directed by Isao Takahata (most known for the non-Ghibli film Grave of the Fireflies), follows a 27-year old woman as she reconnects with the countryside and becomes nostalgic for a past that the metropolis is quickly forgetting.

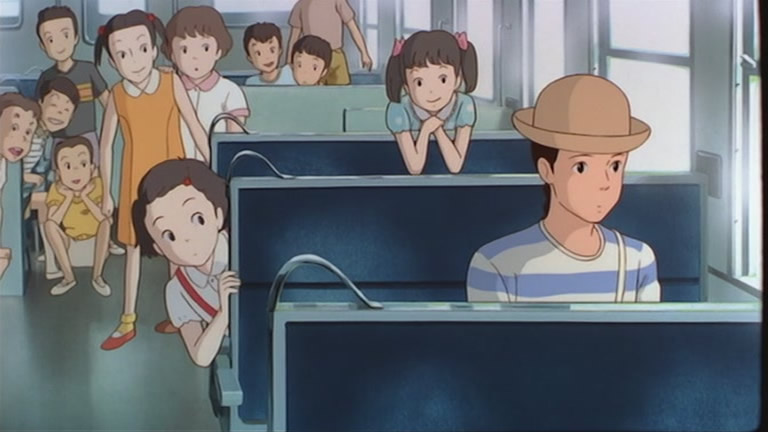

Only Yesterday is steeped with nostalgia in every scene — it is impossible to talk about this film without saying the word dozens of times, so be prepared. In the simplest way this is done through flashbacks of Taeko as a 10-year-old girl, scenes which take up a majority of the film’s narrative. We see a number of wonderful vignettes like the family’s first experience eating pineapple and Taeko’s first love, a boy from a different class, which is set up through a number of pranks by other mischievous students. These stories are personal, beautiful and poetic, filled with drama and levity. Artistically, the sequences of young Taeko are drawn and painted with softer edges and a more pastel driven color scheme. The backgrounds of these scenes almost look like watercolor, a wonderful effect in capturing the tone and ideas of nostalgia and memory. This is contrasted with the sharper animation of the present, especially in the city, with straighter lines and bolder edges.

In the present, Taeko has politely rejected a marriage proposal and taken a vacation from the city to pick safflower (a primary ingredient in making clothing dyes and rouge) in the country. Harkening back to the ever-present themes of nostalgia, even Taeko’s summer job has become obsolete through technology — machines are able to pick the flowers much more quickly and much more cheaply. Also, it is noted that people have begun to leave the Japanese countryside for the big cities. Looking back to her life as a child is certainly done as a means to be nostalgic, but it is also an explanation as to why she loves the countryside so much — she was very rarely gotten the opportunity to escape her troublesome young life in the city. She may be trying to escape that life, but we also have learned that these are the moments which have defined her as a woman. By the end of the film, at the end of her getaway, she is forced to make a decision — will she leave her established life in the city for the only place she feels she truly belongs? The conclusion of the film beautifully brings together all the characters from the film, past and present, in a joyous display of nostalgia and memory.

Only Yesterday is an incredibly simplistic story, one which doesn’t really beg to be animated. Many of Ghibli’s films involve strange creatures, elaborate dream sequences or (in the case of the previously reviewed film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind) impossible-to-film action setpieces. A film so modest and light raises the question: why animation? At its heart, Only Yesterday is a fairly standard coming-of-age romance, and we’ve seen many films looking back to tell nostalgic tales of youth. If Only Yesterday was remade as live-action it would be comparable, but certainly not as memorable. Though maybe unnecessary, the animation of the film brings it to an artistic height that wouldn’t have otherwise been there. Perhaps the small-scale drama isn’t groundbreaking, but the animation is beautiful.