Rohmerathon: La collectionneuse, by Scott Nye

From the very first frames, we’re in uncharted territory for Rohmer. In full color, a young bikini-clad girl walks along a beach. The sun is shining, the waves lap upon the shore. There is no voiceover, and the sounds – the waves, her feet along the ground, a stray seagull – seem attained at the moment of the images. She pauses, posing somewhat for us, Rohmer’s camera observing her face, her stomach, her back, her knees, her collarbone; it gazes up and down her body, pausing briefly on her chest. The title card informs us this is Haydée (Haydée Politoff), but we’ll not really know much about her for a little while longer. Even then, this dissociative introduction to her is instructive, as we run up against limitations of perception, perspective, and attention in trying to get to know her.Unlike previous Rohmer films, she is the first character we meet, but she is not our protagonist. That would be Adrien (Patrick Bauchau), introduced two scenes later as he quarrels with his lover over whether to spend their vacation in London – where she is heading – or the Riviera, where he is destined. He’s an optometrist hoping to become an art dealer; because he has business to conduct in Saint-Tropez (and, as we’ll discover, is the stubborn sort), they go their separate ways. He is determined to spend this time relaxing for, by his own estimate, the first time in ten years. His friend Daniel (Daniel Pommereulle), also staying at the villa, seems accommodating and complementary. He’s a bit more on the bitter side, but their rapport is never less or more than friendly; ideal for a vacation.Enter Haydée, also given permission by the never-seen, often-mentioned Rudolphe to enjoy the use of his massive home. She’s a student enjoying her youth (Politoff was around twenty at the time of filming; her co-stars a good deal older), which means a good number of boys and parties. The men, thinking themselves enlightened and having enjoyed innumerable affairs themselves, try desperately to give no indication of judgment, but quickly fall into a pattern of despising Haydée for her freedom and trying to exploit it to their sexual gain. By the end, she’ll give into both of them, but in Rohmer, there are still a few steps between consent and consummation.

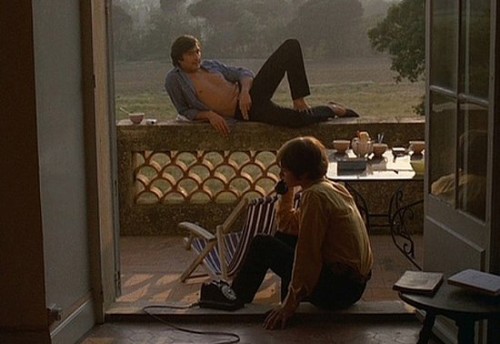

From the very first frames, we’re in uncharted territory for Rohmer. In full color, a young bikini-clad girl walks along a beach. The sun is shining, the waves lap upon the shore. There is no voiceover, and the sounds – the waves, her feet along the ground, a stray seagull – seem attained at the moment of the images. She pauses, posing somewhat for us, Rohmer’s camera observing her face, her stomach, her back, her knees, her collarbone; it gazes up and down her body, pausing briefly on her chest. The title card informs us this is Haydée (Haydée Politoff), but we’ll not really know much about her for a little while longer. Even then, this dissociative introduction to her is instructive, as we run up against limitations of perception, perspective, and attention in trying to get to know her.Unlike previous Rohmer films, she is the first character we meet, but she is not our protagonist. That would be Adrien (Patrick Bauchau), introduced two scenes later as he quarrels with his lover over whether to spend their vacation in London – where she is heading – or the Riviera, where he is destined. He’s an optometrist hoping to become an art dealer; because he has business to conduct in Saint-Tropez (and, as we’ll discover, is the stubborn sort), they go their separate ways. He is determined to spend this time relaxing for, by his own estimate, the first time in ten years. His friend Daniel (Daniel Pommereulle), also staying at the villa, seems accommodating and complementary. He’s a bit more on the bitter side, but their rapport is never less or more than friendly; ideal for a vacation.Enter Haydée, also given permission by the never-seen, often-mentioned Rudolphe to enjoy the use of his massive home. She’s a student enjoying her youth (Politoff was around twenty at the time of filming; her co-stars a good deal older), which means a good number of boys and parties. The men, thinking themselves enlightened and having enjoyed innumerable affairs themselves, try desperately to give no indication of judgment, but quickly fall into a pattern of despising Haydée for her freedom and trying to exploit it to their sexual gain. By the end, she’ll give into both of them, but in Rohmer, there are still a few steps between consent and consummation. Her youth, arguably the trait that most allures Adrien and Daniel, also makes her less susceptible to their advances. Her affairs seems to center around boys her own age. Like her, they aren’t looking much beyond the present day, and are enamored with the simple activities that most compel her. Adrien, by contrast, can’t even relax as he intends, constantly looking over his shoulder to see if Haydée is observing his physique, following him, or even aware of his existence. Rohmer isn’t often praised for his aesthetic rigor, but a shot of Adrien lounging with his shirt wide open, staring at Haydée as she chats idly on the phone, amusingly sums up the tension between them. Everything is a mission for Adrien, a chance to “win.” His vacation is half a business trip. This is a man too serious about life to allow for a simple fling.

Her youth, arguably the trait that most allures Adrien and Daniel, also makes her less susceptible to their advances. Her affairs seems to center around boys her own age. Like her, they aren’t looking much beyond the present day, and are enamored with the simple activities that most compel her. Adrien, by contrast, can’t even relax as he intends, constantly looking over his shoulder to see if Haydée is observing his physique, following him, or even aware of his existence. Rohmer isn’t often praised for his aesthetic rigor, but a shot of Adrien lounging with his shirt wide open, staring at Haydée as she chats idly on the phone, amusingly sums up the tension between them. Everything is a mission for Adrien, a chance to “win.” His vacation is half a business trip. This is a man too serious about life to allow for a simple fling. Adrien’s distraction is all the more pitiable because he’s practically living in paradise. As captured by cinematographer Néstor Almendros, every rock, leaf, weed, flower, and drop of water seems to have been painted for these three. They wander the field surrounding the house, lounge under trees, wade in the water, and bask in the sun, but appreciate none of it, too laser-focused on their libido and potential for attracting a mate. The French Riviera is a familiar setting for idyllic fiction, the splendor contrasting with the limitations of a character’s worldview. In Saint-Tropez, Rohmer has found a less-explored corner (the only people who cross paths with the three main characters are those they invite), heightening the sense of claustrophobia in being trapped in wide-open spaces. The house is plenty huge, but should one want an escape, a gigantic field surrounds it and the beach is only a short walk away. Yet the characters return again and again to the salon, to the kitchen, to their bedrooms, to areas where they expect to find and torture one another with their incompatibility. When Haydée can’t find a ride from one of her flings one evening, Adrien refuses to drive her, merely to refuse her an avenue by which she would not be in his company.Even Haydée, certainly the most innocent of the three, purposefully teases her sexuality while denying to herself the potential for where it might lead. It’s not that she’s to blame for Adrien and Daniel’s unwanted advances, but there’s an understandable lack of foresight in what, exactly, she expects to do with them when she flirts. She doesn’t really seem to much like either of them, aside from brief instances when they happen to amuse her. Her boredom as she’s stuck listening to Daniel insult her extensively over this push-pull instantly marks where Rohmer’s sympathies lie; for as much as women may frustrate men, men do far worse in return.The ending, free of the suggestions of warmth and forgiveness that so endeared The Bakery Girl of Monceau, Suzanne’s Career, and, soon, My Night at Maud’s, are entirely absent from La collectionneuse. This bitterness and cynicism would come into play more in the later entries in the Moral Tales series, so it is little surprise that Rohmer would have shot Maud first if its lead, Jean-Louis Trintignant, had been available, but he made incredible use of the time he had with this gorgeously-photographed slice of ironic fiction. La collectionneuse marks a massive turning point for Rohmer, emphasizing the beauty of the world to contrast with his shortsighted characters, and gradually doing away with the voiceover narration when a look or gesture suggests far more. That this aesthetic evolution should be paired with a retreat in empathy – or perhaps simply a greater emphasis on interrogation – makes for an interesting entry in the “Moral Tales.” In many ways, it seems like the three color films in the series are of a certain piece, while the three black-and-white ones are of another; it will be interesting to see if this observation holds as I continue.

Adrien’s distraction is all the more pitiable because he’s practically living in paradise. As captured by cinematographer Néstor Almendros, every rock, leaf, weed, flower, and drop of water seems to have been painted for these three. They wander the field surrounding the house, lounge under trees, wade in the water, and bask in the sun, but appreciate none of it, too laser-focused on their libido and potential for attracting a mate. The French Riviera is a familiar setting for idyllic fiction, the splendor contrasting with the limitations of a character’s worldview. In Saint-Tropez, Rohmer has found a less-explored corner (the only people who cross paths with the three main characters are those they invite), heightening the sense of claustrophobia in being trapped in wide-open spaces. The house is plenty huge, but should one want an escape, a gigantic field surrounds it and the beach is only a short walk away. Yet the characters return again and again to the salon, to the kitchen, to their bedrooms, to areas where they expect to find and torture one another with their incompatibility. When Haydée can’t find a ride from one of her flings one evening, Adrien refuses to drive her, merely to refuse her an avenue by which she would not be in his company.Even Haydée, certainly the most innocent of the three, purposefully teases her sexuality while denying to herself the potential for where it might lead. It’s not that she’s to blame for Adrien and Daniel’s unwanted advances, but there’s an understandable lack of foresight in what, exactly, she expects to do with them when she flirts. She doesn’t really seem to much like either of them, aside from brief instances when they happen to amuse her. Her boredom as she’s stuck listening to Daniel insult her extensively over this push-pull instantly marks where Rohmer’s sympathies lie; for as much as women may frustrate men, men do far worse in return.The ending, free of the suggestions of warmth and forgiveness that so endeared The Bakery Girl of Monceau, Suzanne’s Career, and, soon, My Night at Maud’s, are entirely absent from La collectionneuse. This bitterness and cynicism would come into play more in the later entries in the Moral Tales series, so it is little surprise that Rohmer would have shot Maud first if its lead, Jean-Louis Trintignant, had been available, but he made incredible use of the time he had with this gorgeously-photographed slice of ironic fiction. La collectionneuse marks a massive turning point for Rohmer, emphasizing the beauty of the world to contrast with his shortsighted characters, and gradually doing away with the voiceover narration when a look or gesture suggests far more. That this aesthetic evolution should be paired with a retreat in empathy – or perhaps simply a greater emphasis on interrogation – makes for an interesting entry in the “Moral Tales.” In many ways, it seems like the three color films in the series are of a certain piece, while the three black-and-white ones are of another; it will be interesting to see if this observation holds as I continue.