Sundance 2021: I Was a Simple Man, by David Bax

In its opening scene, in which two old Hawaiian men swap nostalgic memories while peppering their speech with Pidgin words, Christopher Makoto Yogi’s I Was a Simple Man may bring to mind Steve McQueen’s recent Small Axe anthology, which highlighted a different underrepresented community and similarly refused to employ subtitles for the patois spoken. And certainly Yogi does provide us with a rare glimpse of Honolulu as it appears to the native residents of its lower income outskirts. But, as the film invites you deeper into its recesses, it becomes something else, something uniquely metaphysical, devastating and beautiful.

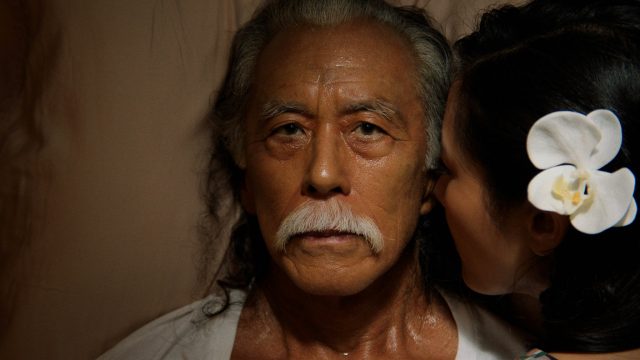

Masao (Steve Iwamoto) is an elderly man who knows he is soon to succumb to illness, leaving behind three adult children. His youngest (Nelson Lee) is still unable to look after himself, while his daughter (Chanel Akiko Hirai) begrudgingly helps out in between taking care of her own large family. His other son lives somewhere on the mainland and has no apparent interest in coming to visit, even as Masao’s days wind down. As Masao awaits death, eventually becoming bedridden, he relives conversations with his late wife, Grace (Constance Wu), and has a few new ones with her ghost to boot. Throughout, he is accompanied by a cute mutt who seems not to know or care for the bounds of time or reality.

So we’ve got an old man on the brink of death conversing with the revenants of his family members. It wouldn’t be incorrect to say that I Was a Simple Man owes a debt to Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.

Yogi achieves some of that movie’s same stillness and even some of its horror-adjacent sense of foreboding. But, again, this film has its own singular mind and often opts for a deep, mournful contemplation instead of inquisitiveness and whimsy.

That’s because, in a way, Masao is as much symbol as character. Men and women his age, the last generation of native Hawaiians to have grown up before statehood, are now dying off. Grace (in what is clearly no narrative coincidence) even died on the same day as the statehood celebration parade. Men like Masao–and the pieces of him that he passed on to future generations–didn’t just switch over to being American. The United States of America did not suddenly stop being colonizers because they declared Hawaii a state. That pain and trauma continues to echo through bloodlines.

I’m a little confused: are these characters supposed to be indigenous Hawaiians or east Asians?

I thought the former. Maybe I’m wrong.

– David