TCM Classic Film Festival 2021: Part Two, by David Bax

1947’s T-Men is one of a flurry of propaganda movies made in the 1940s and 50s with the cooperation of various law enforcement agencies. Like 1949’s Trapped, this one’s about treasury agents tracking counterfeiters. Other examples include 1954’s Down Three Dark Streets (FBI) and 1953’s City That Never Sleeps (Chicago PD). Those movies have their charms and qualities but they don’t have what T-Men has: Director Anthony Mann. Mann’s framing and lighting are quintessential noir and his penchant for brutish, de-sensationalized violence is on display from the murder of an informant in the movie’s opening scene. Meanwhile, Los Angeles locations like Chinatown and the Original Farmers Market are highlighted (even if the latter seems to have been accomplished via process shots). And if exteriors aren’t your thing, the interiors are a delight too, including a montage of shirtless Dennis O’Keefe visiting every Turkish bath in the city looking for a counterfeiter who’s known to enjoy a nice steam. There’s no escaping the propaganda, from the corny third person narration to the many references to the prosecution of Al Capone, clearly still a feather in the agency’s cap over fifteen years later. But Mann rises above–or sinks below, given the underworld setting–the restrictions of this microgenre.

Hey, speaking of the underworld, there it is right there in the title of the next movie! Samuel Fuller’s Underworld U.S.A. really stresses the world part of the title, building from its opening scene–in which a young kid takes the watch and wallet off a drunk who’s blacked out in the alley before then getting bloodied and robbed himself by an even younger kid–a whole shared environment of sadistic violence and men and women both who would cut your throat if it gave them a half a leg up. That kid from the beginning, Tolly, sees this first hand when he watches his father beaten to death by his own criminal associates right in front of his eyes and dedicates his life to getting vengeance. Once he’s grown up (and played by Cliff Robertson) and sent to prison, he gets his chance when he meets the ringleader, whose deathbed confession gives him the dirt he needs on the remaining killers. Once released, he sets out to undo them, one by one. Underworld U.S.A is, by turns, grim (the murder of a child comes into play), goofy (a doctor refers to pills as “joy powder”), ironic (a dying man knocks over a trashcan that says “Keep Your City Clean” and then bleeds out among the refuse under a sign encouraging citizens to give blood) and, it should be said, possibly a little homophobic (one of Tolly’s targets may be coded as gay, depending on which definition of the word “punk” you think the movie’s going by). The whole movie feels dangerous, itself a product of the world it’s created.

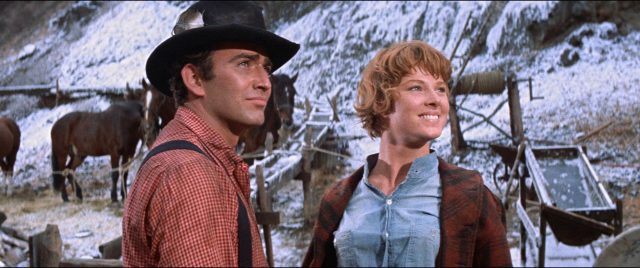

From one Sam to another, we now go to 1962’s Ride the High Country, an early Western from Sam Peckinpah. Only his second feature, it’s not quite the full-blown revisionism of The Wild Bunch–Joel McCrea’s Steve Judd is a hero, not an anti-hero–but Peckinpah’s interest in a version of the west where morality is more a fader than a toggle is already clear; there’s even a narrow-minded holy roller played by R.G. Armstrong on hand to represent the folly of black and white thinking. Judd reteams with his old partner Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott) and Gil’s new protégé, Heck (Ron Starr) on a job to transport a shipment of gold through dangerous territory. Gil and Heck are the ostensible villains, since we learn early on that they plan to steal the gold themselves. But that changes when they reach the camp where they’re to pick up the gold and meet a clan of brothers (played by, among others, genre greats Warren Oates and L.Q. Jones) who represent a version of villainy that’s dumber, more dangerous and more commonplace. Even apart from morality, Peckinpah is eager to upset expectations in ways big and small. The core trio have their first meeting, for instance, in a Chinese restaurant, something that very well may have been less rare in the real old west than the Hollywood version. More crucially, the ostensible leads disappear from the movie for a sizable portion of the second half while Peckinpah turns his attention to the story of a young woman (Mariette Hartley) who’s run away from her strict father only to find herself surrounded by even less kind men. Ride the High Country may still have a white hat hero at its center but the world he’s fighting for may not be worth the effort.

Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s It’s Always Fair Weather (1955) is one of those movies where it’s hard to talk about it without just listing all the good parts because that’s all the movie is, a series of good parts strung together. It’s grand, lavish fun that never goes too long without unleashing another song and dance number that threatens to bounce through the screen. So which ones should I mention? Well, there’s the one with Kelly rollers kating around an absolutely massive city street set crammed with people and cars while he sings a happy tune and then tap dances on his skates. And there’s the inventive one where the vocals are a series of inner monologues and the only choreography plays out on the faces of stars Kelly, Dan Dailey and Michael Kidd (the latter a Broadway legend who only appeared in a handful of films, just like Dolores Gray, who also runs away with the movie on a couple of occasions). But I think my pick for the best number would have to be one that Kelly’s not even in, in which Cyd Charisse (in a possible career best role), wearing a jade green outfit that’s tight on top but with a skirt made for kicking and swinging, twirls, jumps and practically flies around a boxing gym with a full chorus of dancing, singing palookas backing her up. Yeah, that one’s the best. Until I watch it again and change my mind.