David’s Movie Journal 1/25/12

Due to the unusually large (for me) amount of movie-watching I’ve been doing lately, I’m once again a bit behind on these. What do you care? Here’s three movies I watched.

Weekend

Andrew Haigh’s tiny, low-budget, intimate film Weekend has more in common than you’d think with James Cameron’s epic, expensive, grand film Titanic. In both cases, two young people meet and become smitten with each other. That initial infatuation then grows exponentially when they realize their affair will likely be forced to end very soon. In Titanic, it’s because they’re on a sinking luxury ship in the middle of the North Atlantic. In Weekend, it’s because one of the pair is moving to Portland, Oregon on Sunday.

Given that the film takes place in Nottingham, in England’s Midlands, that impending relocation is a sizable obstacle. Haigh makes the perfect choice by not introducing it until about halfway through the film. If we knew that information from the beginning, we might be pleading internally for our primary lead, Russell, not to get so invested in the soon to depart Glen. After all, our initial reaction to him is that he’s a bit smug and immature. Yet he is refreshingly honest with himself and others in a way that unveils his innate intelligence and bestows on him an allure that is noticed by no one more so than Russell.

Despite two great lead performances and characters, this is ultimately Russell’s film. We see how, in ways with which we are likely familiar, he changes or obscures parts of himself in the presence of Glen. These are, after all, things we all do in the early stages of a relationship. But we also see how this brief encounter will leave Russell forever altered. That’s something that doesn’t happen with every person you’ve known for two days. Yet when we do meet someone who will change our lives in some way, we generally don’t see it coming. Haigh’s film may be small and intimate but then so are most of the most important things in one’s life.

The Artist

I tend to get nervous in the minutes before a movie starts. Not at home, of course; I refer only to my theatergoing experiences. I start to cast nervous glances at the more talkative members of the audience, convincing myself that they won’t cease once the program begins. My suspicions are upheld more often than I’d like. My nervousness came to a peak as I waited for Michel Hazanavicius’s The Artist to commence. Eventually, I came to a point where I considered standing up, turning around and shouting, “Just in case one of you dipshits was too stupid to find out anything about the movie you’re about to see, this is a silent film! So make your peace with it now or get the fuck out and leave the rest of us to enjoy ourselves!” At the last moment, though, it occurred to me that such action would be condescending on my part, not to mention that it would likely cast a pall over the room that could possible hinder everyone’s ability to appreciate the film. Instead I opted to aim for some sort of meditative state that would allow me to focus on the film and rise above any potential noise from disgruntled philistines.

If you’ve seen The Artist, then you likely know that none of this was necessary. This film is a crowd-pleaser. I don’t only mean that it entrances its audience too much to talk. I also mean that I myself was too rapt to have even notice. Despite its lack of dialogue, I don’t think I’d have noticed the usual crinkling popcorn bags and the coughs of what I’m assuming are uncovered mouths. Like one of its most obvious antecedents, Singin’ in the Rain, it is a celebration of what cinema can do and be.

Admirers and critics of the film alike will generally agree with that summation. The conversation must then turn to whether its joy is worthwhile and earned or if it is cheap sentimentalism. The film makes headway toward legitimacy by telling an involving story in the midst of its cinematic flights. It’s a mostly standard retelling of A Star Is Born but it’s relayed with skill and commitment. Hazanavicius is not merely romanticizing a bygone era of film. He’s exalting the art of film itself. Much like Edgar Wright, Hazanavicius wields a firm and excitingly clever control over form. He uses camera placement and movement, insert shots and various other techniques I won’t spoil for you here in order to make jokes and otherwise delight the viewer. It makes for a fun and fast 100 minutes but it also makes a good case for the singularity of cinema as an art form.

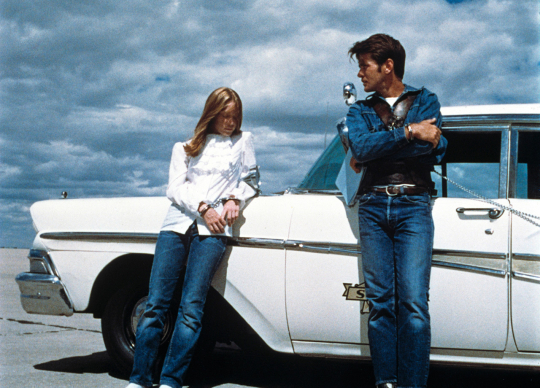

Badlands

This is one of the few not-new movies that I’ve watched recently though it was, embarrassingly, new to me. I had, of course, heard many great things over the years but had never gotten around to actually watching Terrence Malick’s first feature film.

Early on, I found myself surprisingly underwhelmed. Not because the filmmaking was more conventional than the Malick of recent vintage but because I was not intrigued by Sissy Spacek’s character, Holly. This impressionable, weak-willed, infantilized young woman displayed almost no agency of her own. She seemed like a somewhat sexist screenplay construct created because Martin Sheen’s idealistic sociopath with his heads in the clouds and his finger on the trigger, Kit, needed a dame to whom he could soliloquize.

What eventually became clear was the fact that Malick introduced her this way on purpose. As the film went on, I began to realize that this was as much Holly’s story as Kit’s, if not more so. When we first meet Holly’s father, it is a warm, playful moment between the two of them in the backyard. Then we learn that he doesn’t approve of Kit. Neither would most of us, I imagine. And then, to punish Holly, he shoots and kills her dog. It’s a shocking moment, to be sure, but by the time it comes around, we haven’t developed any negative feelings toward the father. We are even perhaps predisposed to sympathize with him. It’s only after Kit kills the man and, in many ways, replaces him in Holly’s life that we begin to understand the submissive way Holly has been conditioned to react to men. The rest of the film is about her acquiring independence. While Kit is dramatically careening toward the romantic and violent ending he’s writing for himself, Holly is slowly approaching a true beginning.