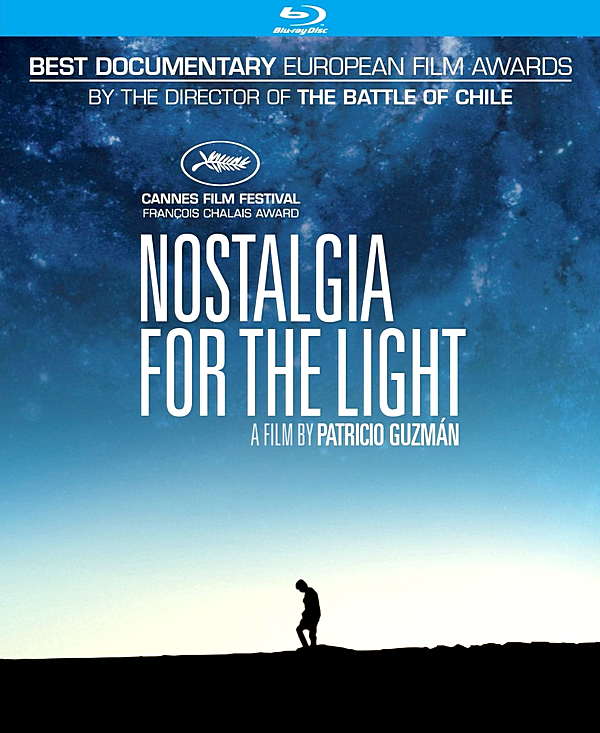

Home Video Hovel: Nostalgia for the Light

Nostalgia for the Light starts out with a very tight static shot on some wheels rolling on a circular track. Director Patricio Guzman then cuts to a series of ever-widening shots until we are able to behold the massive telescope that has been the subject of this opening sequence. The aesthetic and thematic mission is immediately obvious – in a scant 90 minutes, Guzman’s concerns will range from the work of a small group of women to the unimaginably cosmic. Near the end of his film, Guzman admits that some viewers might have found the more human portions of his film to have little significance against the segments exploring the unending universe, but he’s wrong the even ask that question. Right away, we understand that everything is connected; everything is important, and Guzman makes connections between Chilean history and the furthest reaches of the universe that seem impossible at face value, but all too natural in his presentation.

That’s about all I’ll say on the actual film, partially because this is a review of the Blu-Ray but mostly because David already wrote up a proper review with which I am entirely in agreement. It’s an absolutely staggering accomplishment, and one of the best films I’ve seen all year. It provoked me to think about subjects I’ve never considered, and to delve further into others from angles that were entirely new to me. I cannot possibly recommend it high enough.

It’s also an aesthetic marvel, save for what I’m chalking up to technical limitations. I couldn’t find confirmation of this anywhere, but based on the artifacts on the Blu-Ray (chiefly when the camera or its subject moves quickly), I’d guess it was shot on a lower-end high definition camera. So while most of the images are lovely (Guzman is a fan of the static shot, which suits his medium), some do suffer. The transfer is also encoded at 1080i, which could account for some of these issues. But I have to stress that these shots are few and far between, and that otherwise the Blu-Ray represents a beautiful film, well…beautifully.

On the audio side, get ready for complaints from your neighbors. I watch a ton of movies on DVD and Blu-Ray, and have a standard level at which I set my speakers. I had to turn it to half that to get it to the level I’m used to, but I decided to give it a little extra kick, because hey, why not. The sound design, not typically an aspect of much note in documentary filmmaking, is astounding here, and I relished taking in every detail of it. From the classical musice to the grinding of the gears in the telescope to the sound of footsteps on rock-hard desert ground, the Blu-Ray brought it all powerfully to life. Turn your system down a notch or two and take it all in.

All of the film’s dialogue is in Spanish, but English subtitles are provided. In fact, you can’t turn them off – sorry, Spanish speakers!

On the special features side, the Blu-Ray presents what they label as documentaries, but they were clearly shot to be used in the film (the score is the same, the shot structure is the same, and a small, unique special effect used in the film is applied to many of these). I’m glad Guzman had the chance to go back to this material, as it does enhance one’s appreciation of his subject and thesis, even if it’s easy to see why he cut it. It’s all fairly tangential, and would disrupt the gentle flow of the film. But we get to see it here now, so everybody wins!

Maria Teresa & The Brown Dwarf, Jose Maza, Sky Traveler, and Oscar Saa, Technician of the Stars all center on individuals working in the field of astronomy. Teresa is an astronomer who first discovered the “brown dwarf,” a star too small to have yet “caught fire.” Guzman compliments her fascination with the stars with her side passion for cross-stitching portraits of loved ones, showing that both demonstrate how tiny movements and objects create larger tapestries (a theme explored further in the film. Maza spends most of his time on dark energy, more of a theoretical subject than anything else (one in which science begins to approach philosophy, a fascinating intersection Guzman also explores), and provides a good outlet for some special effects work on Guzman’s part. Saa, meanwhile, is a telescope technician, who further explains the massive telescope that Guzman often returns to in Nostalgia for the Light. He talks about the harsh process astronomers go through to even gain access to it, noting that many abandon the field altogether when they miss an event one night and are forced to reschedule for the same time next year.

Chile, A Galaxy of Problems dives further into the national effort to forget Chile’s very recent past. It can be a tad repetitive, but the depth and breadth of material is vital for those of us who, I hate to admit, aren’t terribly familiar with Chilean history. Guzman illustrates how not only the bureaucratic attitude, but even the education system, seeks to sweep so much of their country’s history under the rug.

The most delightful documentary is Astronomers from my Neighborhood, which looks at the sort of home-grown astronomy fields that crop up around larger institutions. It starts by visiting a man who makes telescope parts in what seems to be a shed, but spends the bulk of its time with Guillermo Fernandez, who built a whole observatory in his back yard, using spare parts, over the course of seven years. His chair, which he can electronically move up and down, includes parts from a car and a sewing machine, and he even installed a miniature toilet so he wouldn’t have to go up and down the steps every time, as he put it, “nature calls.”

All in all, it’s a very good disc. The image quality perhaps could have been better, but the issues are confined to a few minutes of screen time, and the film itself is so overwhelmingly great it’s impossible to fixate on such minor issues. The special features acutely explore individual themes of the film, and work very well as pieces unto themselves. The disc comes highly recommended, and is an absolute must to rent.