There There: Scheme to Scheme, by David Bax

After his deservedly acclaimed, semi-experimental triumph Computer Chess in 2013, mumblecore godfather Andrew Bujalski’s films rose in visibility, production value and star power; see 2015’s Guy Pearce-led Results and 2018’s Regina Hall-starring Support the Girls (which remains the director’s masterpiece). So, in some ways, Bujalski’s new iPhone-shot hyperlink anthology movie There There is a return to the lo-fi roots of Funny Ha Ha et al. But the big name actors remain. Of course, there’s no reason that sort of thing shouldn’t work. Steven Soderbergh’s done it a bunch of times. But the inbetweeniness of it all is a metaphor for a movie that ultimately ends up a shapeless shrug, unable to argue in favor of its own form or content.

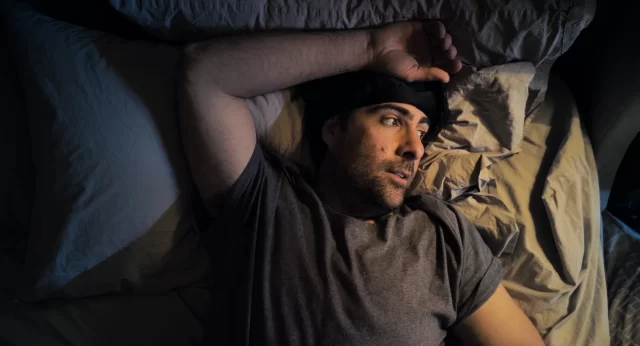

In the beginning, There There appears to be continuing his interest in making films chiefly about the female experience (as evidenced by both Funny Ha Ha and Support the Girls). In the first scene, Lili Taylor plays a woman who has woken up in bed next to a one night stand (Lennie James) and, during the time it takes him to dress and get ready to leave, bounces back repeatedly between infatuation and caution at her own vulnerability. In the next scene, we see her meet with her Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor (Annie La Ganga) where she continues to discuss her feelings, revealing more and filling in the blanks of her halting early morning conversation. From there, we see La Ganga’s character attend a conference with her teenage son’s teacher (Molly Gordon).

And so it goes from there, each two-hander passing one character on to the next like a baton. These early scenes are the best, detailing individual women’s struggles to deal with their own daily emotional load. As the film expands to include characters like Jason Schwartzman’s tech-bro lawyer and dad struggling with a case of conscience, the film becomes diffuse as opposed to panoramic.

Bujalski has always bucked the stereotype suggested by the label “mumblecore,” which carries with it an implied accusation of navel-gazing. But that term has never been a fair one, especially as applied to a genuinely important movement in American independent film. In any case, his movies are full of varied human beings, each with their own distinct mélange of complications, flaws and difficulties. They’re often not easy to like but Bujalski makes them impossible not to love by virtue of showing them to you through the lens of his own humanism. And, once again, There There proves to be a stumble for him. Anthologies are almost always uneven by nature but the highs do not outweigh the lows, especially since the latter become more numerous as the film drags on.

Also included are some legitimately enjoyable musical interludes. In between vignettes, we watch what appears to be live footage of composer Jon Natchez (The Climb) performing pieces of the score.

These interstitials are cool but they seem designed to break up the repetitive structure of the film. Instead, they only reinforce it. There There seems like Bujalski’s answer to a film like Dustin Guy Defa’s Person to Person. But where that film was beautifully organic, this one is purely schematic.